Search for Articles

Article Agriculture Food Sciences Information Sciences Psychology Psychology and Education

Why do you recall that smelly food? Effects of childhood residence region and potential reinforcing effect of marriage

Journal Of Digital Life.2026, 6,2;

Received:June 8, 2025 Revised:October 20, 2025 Accepted:November 23, 2025 Published:January 27, 2026

- Yoshinori Miyamura

- Technology Research & Innovation, BIPROGY Inc.

- Ai Ishii

- Technology Research & Innovation, BIPROGY Inc.

- Atsushi Oshio

- Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences, Waseda University

Correspondence: yoshinori.miyamura@biprogy.com

Abstract

Little is known about why smelly foods have been maintained for long periods of time despite their unpleasant smell. Previous research suggests that regional background and family environment during upbringing influence food selection. Based on those findings, we hypothesized that living in a region where traditional smelly foods are produced and consumed during one's childhood would enhance the recall of such foods in adulthood. Additionally, we proposed that this childhood experience would positively influence the effect of marriage on an individual’s recall of smelly foods. We selected kusaya as the chosen smelly food and examined how, as the main effect, living in the Kanto region of Japan until the age of 20 impacts an individual’s kusaya recall. Furthermore, we explored the moderating effect of this upbringing on kusaya recall and marital status by sequentially inputting variables into a logistic regression model. Both effects were confirmed. This study contributes to the understanding of how characteristic smelly foods can be preserved by clarifying the factors that enhance their recall, using kusaya as an example.

1. Introduction

Human appetite is enhanced by sensory cues, such as odor (Morquecho-Campos et al., 2020; Ramaekers, Boesveldt, Gort, et al., 2014; Ramaekers, Boesveldt, Lakemond, et al., 2014), and controlled by proteins (Morquecho-Campos et al., 2020) and calories (Zoon et al., 2016). Foul smells emanating from food provide information about the presence of uncooked, putrid, or poisonous substances. However, we somehow continue to eat smelly food. For instance, surströmming, a lightly salted fermented fish dish from Sweden, was invented owing to limited salt availability (Belleggia et al., 2020; Skåra et al., 2015). Similarly, in Japan, a lack of salt in fish processing led to the creation of a fermented fish dish known as kusaya (Simidu et al., 1967). Although salt deficiency is no longer an issue in Sweden or Japan, surströmming and kusaya are still consumed.

Why are these malodourous foods still consumed? We considered the influence of the local area on residents’ food choices, because the region may impact the integrated conceptual model of food choice (Chen & Antonelli, 2020). According to Chen and Antonelli (2020), food choice is influenced by a combination of factors, including internal factors (sensory and perceptual features), external factors (information, social environment, and physical environment), personal state (biological features and physiological needs, psychological components, habits, and experiences), cognitive factors (knowledge and skills, attitude, likes and preferences, anticipated consequences, and personal identity), and sociocultural factors (culture, economic variables, and political elements). The relationship between region and food may also influence these food choice factors. For instance, external food factors may include proximity to the production region and sociocultural factors may include food culture traditions. Likewise, food accessibility may influence the personal state factors of habit and experience, and more information about food may influence cognitive factors of choice.

In fact, kusaya, a famously smelly Japanese food, is produced in the Izu Islands, including in its place of origin. Kusaya is consumed primarily in the Kanto region (Fujii, 2011) centered on Tokyo (Edo), where it has been distributed since its origination in the Edo period (Simidu et al., 1967). Funazushi is produced and consumed along the shores of Lake Biwa (Fujii,, 1984). Natto, a fermented soybean product, is now widespread throughout Japan, although previously there were regional differences in its production, processing, and consumption methods (Honma & Ishihara, 1996). These examples indicate that foods considered smelly are likely to continue being consumed in their place of origin and in certain regions closely tied to that origin. We hypothesized that the reason for this is that the memory of smelly foods is formed due to the influence of the region.

We further considered the period from the fetal stage to adolescence to be crucial for the formation of the memories that individuals associate with smelly foods. For example, previous studies have illustrated that fetuses are affected by maternal eating and drinking through the amniotic fluid (Faas et al., 2000, 2015; Hepper, 1995; Hepper et al., 2013; Mennella et al., 2001; Schaal et al., 2000) and, in the case of infants, through breast milk (Hausner et al., 2010; Mennella & Beauchamp, 1993, 1999; Spahn et al., 2019). Examples of foods that can lead to fetal effects during pregnancy include alcohol (Faas et al., 2000, 2015), anise (Schaal et al., 2000), carrot juice (Mennella et al., 2001), and garlic (Hepper, 1995; Hepper et al., 2013). Additionally, infants exhibit altered responses to the flavors of carrots (Mennella & Beauchamp, 1999), garlic (Mennella & Beauchamp, 1993), and caraway (Hausner et al., 2010) after experiencing them through breast milk. Moreover, exposure to garlic in the amniotic fluid during pregnancy has been illustrated to alter eating behavior in eight- to nine-year-old children (Hepper et al., 2013), suggesting that experiencing smelly foods during fetal life through the amniotic fluid may have unexpectedly long-lasting effects.

Children are also more likely to base their food choices on the foods their parents gave them as children, even after they reach college age (Unusan, 2006). For the vast majority of foods, significant associations have been observed between perceived recollection of the frequent consumption of foods in childhood and current preferences in adulthood, including nutritious foods such as vegetables (Wadhera et al., 2015). These studies indicate that dietary habits from fetal development through adolescence influence food choices later in life. Furthermore, since parental food choices may be influenced by regional factors, it is conceivable that children are also indirectly affected by regional influences. Therefore, we hypothesized that the region where an individual spends their childhood through adolescence influences their food memories later in life. Therefore, this study focused on the impact of the sociocultural environment of the residential area on memory formation, rather than the mechanisms of direct food transmission within families.

This study aimed to examine regional influences on the preservation of traditional smelly food in the present day. We posited that children raised in regions where traditional smelly foods are produced and consumed acquire experiences related to these foods through regional influences from the fetal stage through adolescence and, consequently, they are more likely to recall smelly food as adults, with its scent acting as a sensory cue. Hence, it may be easier to recall smelly food when the word “smelly” is used to describe it.

To test this hypothesis, it would be desirable to explore memories of food experiences related to the region. However, people tend to have few memories of events from before the age of 7, and even fewer from ages 3–4 or younger (Bauer, 2015), which could bias recall of when they first encountered smelly food. Therefore, we decided to investigate the effect of region on smelly food recall using place of residence up to the age of 20, instead of smelly food experiences related to the region. Specifically, we tested the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis I: Living until the age of 20 in a region that produces and/or consumes traditional smelly food reinforces an individual’s recall of that food when asked about smelly food as an adult.

Despite the importance of early childhood experiences, we focused on the place of residence up to age 20. The period before age 20 might be spent in a stable food environment based on family and community, making it less susceptible to the influence of personal preferences or choices driven by independence. Furthermore, the legal drinking age in Japan is 20 years or older. Smelly foods, such as kusaya (Fujii, 2011; Nakazato et al., 1995) or funazushi (Fujii,, 1984) are consumed as drinking snacks in many cases. Therefore, this age can be considered a potential transition point between a family-centered diet during the minor years and a social eating environment involving alcohol consumption. In Japan, high school and university graduation occur around age 20, and many individuals leave their family home upon employment or further education, potentially altering their subsequent dietary habits. Therefore, we considered the place of residence before age 20 to most accurately reflect regional influences. Furthermore, in addition to regional influences during adolescence, life events such as marriage may also affect how people recall odorous foods because the family formed through marriage includes non-blood relatives who may have different perceptions of odors and food preferences.

Therefore, we considered the effect of marriage on an individual’s recall of smelly food. Marriage introduces non-blood relatives, such as spouses and in-laws, to the family. These non-blood relatives are more likely to have genetic differences in how they perceive smells (Keller et al., 2007; Lunde et al., 2012; Mainland et al., 2014; McRae et al., 2013; Wysocki & Beauchamp, 1984), potentially leading to differing food preferences (Frank & van der Klaauw, 1994). Since food smells diffuse, differences in smell preferences among family members may make it challenging to eat foods with strong odors.

However, participants may be encouraged to try traditional smelly foods by new family members from the same hometown, and new family members from different hometowns may be interested in foods produced or consumed in the participant’s hometown, giving participants the opportunity to try traditional smelly foods. Participants who experienced these foods as children and have retained memories of them may recall these foods when their new family members offer them or when they try to avoid their smell. We hypothesized that post-marital recall would strengthen childhood memories of traditional smelly foods. In fact, research in mice (Fukushima et al., 2014) and humans (Forcato et al., 2011) depicts that memories can be strengthened through reconsolidation after recall. Therefore, we tested the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis II: People who lived in an area where traditional smelly foods were produced and consumed until the age of 20 improve their ability to recall these foods after marriage.

In summary, the purpose of this study was to test two hypotheses regarding regional influences on smelly food recall to provide insights into why memories of smelly food are passed on in the neighborhoods where these foods originated. Simultaneously, the results may have implications for how traditional smelly food should be preserved in the future.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee for Life Science Research in BIPROGY Inc. (ID: 2020-002, approved with conditions on March 24, 2020; conditions were removed on May 21, 2020). The survey was conducted via a website from August 6 to September 8, 2021, targeting people living in Japan. The number of recruits was stratified using Basic Resident Registration population data (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Japan, 2021) to approximate age (20–59 years, in 5-year increments), gender, and prefecture of residence of the participant group to be recruited to the Japanese population distribution.

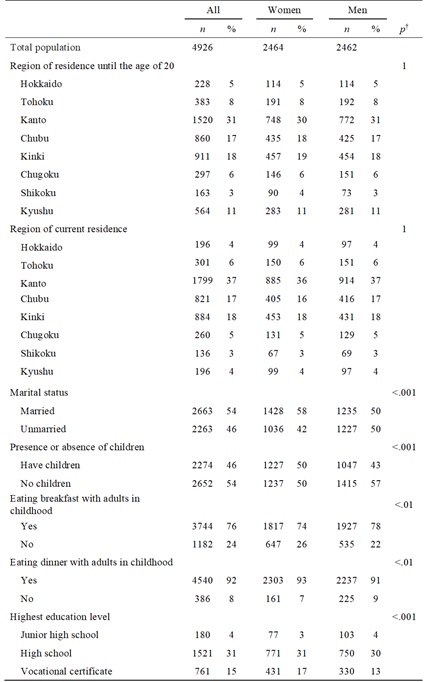

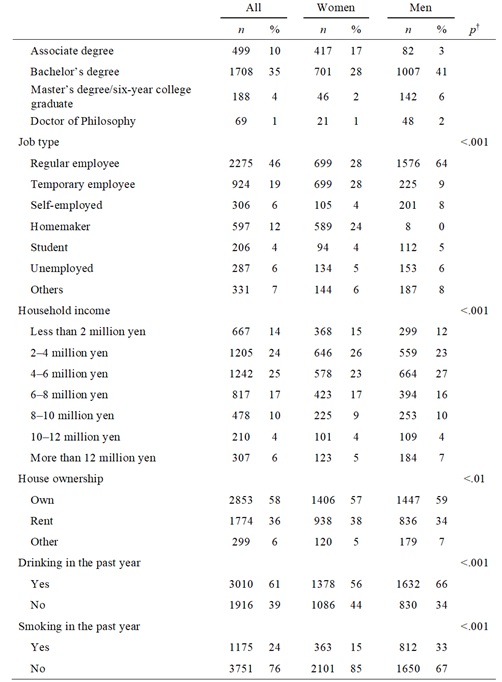

Participants were recruited through an Internet research service (iBRIDGE Corporation, 2021). Web-based instructions were presented to the participants before they completed the questionnaire. We received responses from 5,485 participants, who were all recruited. Finally, data from 4,926 respondents were used for the analysis after excluding fraudulent respondents. Although no personal information was collected, participants were assigned an ID to prevent multiple responses from a single participant (iBRIDGE Corporation, 2021). The participants’ age, gender, marital status, presence of children, occupation, levels of household income, current address (prefecture), and house ownership status were obtained from annual survey data from the Internet research service (iBRIDGE Corporation, 2021). The participants’ demographic information is presented in Table 1.

2.2 Questionnaire

The questionnaire survey was conducted in Japanese. Participants’ recall was measured by determining whether participants could name a type of smelly food. Specifically, participants were asked to name one smelly food in the open-ended response section of the web-based survey. In addition, they were instructed to respond, “I do not know,” if they did not know or could not recall the name of a smelly food.

Additionally, participants were asked to indicate the province in which they had lived the longest before the age of 20, whether they ate breakfast and/or dinner with adults during their childhood, their highest level of schooling, and whether they had consumed alcohol or smoked in the past year.

Table 1. Participants’ demographics and characteristics

Note. The median participant age was 42 years (lower quartile = 32, upper quartile = 50) with no significant difference by gender. †p-value of Fisher’s exact test was adjusted for multiple tests using the Bonferroni correction.

2.3 Standardization of food names

To account for individual differences in the level of detail provided in food name descriptions, food names were standardized into simpler, shorter common names. Specifically, we created a thesaurus of food names; similar foods were grouped accordingly. The food names included as entries were sourced from literature on food preferences in Japan (Esumi, 2000; Fuzihara & Banba, 2014; Hatanaka & Nunomi, 2019; Higashiguchi, 2019; Horio, 2012, 2014; Kobayashi et al., 2016; Kosugi & Horio, 2005; Mitsuhashi et al., 2008; Ogawa & Nakazawa, 2018; Shimoda, 2011; Suzuki et al., 2013; Tateyama et al., 2013; Toyomitsu et al., 2004) and the 2015 Standard Tables of Food Composition in Japan (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan, 2015), which was updated in 2019. We used Wikipedia redirection to extract synonyms for the items by identifying words that were redirected to the same page. If a common food name was not included in the thesaurus, it was manually added as an entry. Multiple entries that were considered synonymous were manually combined into one common entry. If the food name mentioned by the participant was not found in the dictionary, it was included in the item list and the thesaurus.

2.4 Natural language processing

The utility of natural language processing has been demonstrated in the taxonomy of olfactory terms (Castro et al., 2013; Dravnieks, 1985; Iatropoulos et al., 2018; Kumar et al., 2015). In this study, we used Iatropoulos et al.’s (2018) olfactory association index (OAI; Iatropoulos et al., 2018) as a reference to create a relationship index between odor terms and food names tailored to the study’s objectives. The procedure is described below.

2.4.1 Odor terms

First, we extracted smell terms as a group of words belonging to the synsets of “smell” search results in the Japanese WordNet (Isahara et al., 2008), excluding 05844282-n (six kinds of quarks) and 14526182-n (the general atmosphere of a place or situation and the effect it has on people). Next, among the smell terms, we extracted, as odor terms, words that were not included in the word groups belonging to the synsets 05714466-n (a distinctive odor that is pleasant), 04980463-n (a pleasingly sweet olfactory property), and 01052248-a (pleasant-smelling), but were included in the word groups belonging to the synsets 05714894-n (a distinctive odor that is offensively unpleasant) and 01053634-a (offensively malodorous) in the Japanese WordNet. Subsequently, smell terms that were listed as unpleasant odors in the Weblio Japanese Dictionary (GRAS Group, 2021) were included. Finally, odor terms that excluded one-character kanji, which are easily used as names of people or stores, were used for the co-occurrence analysis with food names using Twitter (Currently: X) data.

2.4.2 Corpus

We used Twitter data as a corpus, randomly sampled at a rate of 1% from the global timeline over five years, from January 1, 2016, to December 31, 2020. Although the corpus contains tweets from around the world, the natural language processing was only focused on Japanese. The Twitter data were filtered using words commonly found in commercial tweets, resulting in 660,475,069 tweets. These tweets were preprocessed by removing URLs, hashtags, and unnecessary symbols.

2.4.3 Software and dictionary

Apache Solr version 8.5.2 (The Apache Software Foundation, 2021), an open-source full-text search platform, was used to index and retrieve tweets. Since Japanese text does not mark word boundaries with spaces, morphological analysis (word segmentation and normalization) was performed using Solr’s built-in Kuromoji tokenizer (Atilika Inc., 2018). To improve recognition of neologisms and proper names, we used the mecab-ipadic-NEologd dictionary (Sato et al., 2017), a lexical resource for MeCab (Kudo, 2006), a Japanese morphological analyzer. Words that could yield false positives as odor terms were included in Apache Solr’s word removal list.

2.4.4 Relationship index between odor terms and food names

First, we searched for tweets containing both food names and odor-related terms as co-occurrences using Apache Solr. Using MeCab (Kudo, 2006; Kudo et al., 2004) for morphological analysis and CaboCha (Kudo, 2005; Kudo & Matsumoto, 2002b, 2002a) for dependency parsing, we calculated the distance between odor terms and food names based on their grammatical relations. Tweets in which the two terms appeared within an empirically determined distance threshold were retained as co-occurrences. For each food item, we calculated the ratio of tweets mentioning both the food and an odor term to the total number of tweets mentioning that food, counting only one tweet per user. This ratio serves as an index demonstrating how strongly each food is associated with particular odors in people’s tweets.

2.5 Statistical methods

2.5.1 Smelly Food Index

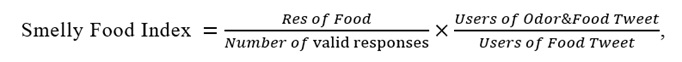

To test Hypotheses I and II, we developed the Smelly Food Index for this study to select smelly foods. The Smelly Food Index was calculated by multiplying the ratio of responses to a descriptive questionnaire for each smelly food with the strength of the relationship between “smelly” and the smelly food’s name in the corpus, including synonyms. We used a Smelly Food Index because a selection based on the descriptive questionnaire alone might include foods that are easy to recall but not particularly smelly. As the number of descriptive questionnaires affects the accuracy of the hypothesis testing, the selection was limited to the top 10 foods in the responses. Specifically, 10 foods with the highest number of responses were selected from the names of foods described as smelly in the questionnaire, and the ratio of each food name in the valid responses was calculated as the food recall index. Next, the relationship index between odor terms and food names was calculated for the 10 foods using Twitter data in Japan from 2016 to 2020 as a corpus (the method is described in Section 2.4.2). Finally, to calculate the Smelly Food Index, we multiplied the food recall index for each food name by the relationship index determined by Twitter data. The formula is as follows:

where Res of Food is the number of responses for each food.

2.5.2 Software

Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, 2018) was used to remove inappropriate responses and convert questionnaire responses into item names using a food thesaurus. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.3.1 (R Core Team, 2022) and R libraries (Lenth, 2023; Lüdecke et al., 2021).

2.5.3 Variables

We selected the smelly food with the highest Smelly Food Index ranking to determine the effect of residence during childhood in the region in which the smelly food is produced and/or consumed on the recall of smelly food. The objective variable was the recall of a smelly food. The explanatory variable was the participant’s residence until the age of 20 in the region that produced and/or consumed the smelly food. Prefectural names were converted to eight major regions in Japan (Hokkaido, Tohoku, Kanto, Chubu, Kinki, Chugoku, Shikoku, and Kyushu) before creating the explanatory variables. The control variables included the following self-reported variables: age, gender, marital status, having children, having breakfast with an adult as a child, having dinner with an adult as a child, seven levels of education, five types of occupation, seven levels of household income, residing in one’s own home, alcohol consumption, smoking, and current region of residence. Marital status was not only used as a control variable but also to examine the moderating effect of place of residence until age 20 on the recall of smelly food.

2.5.4 Hierarchical binomial logistic regression analysis

A hierarchical binomial logistic regression analysis was used to determine the effect of living as a minor in the region in which the smelly food is produced and/or consumed on smelly food recall. A likelihood ratio test of deviance was performed to test whether entering the variables significantly improved the regression model’s fit. We adopted α = 0.05 as the significance level. In Step 1, control variables were entered into the null model. In Step 2, a variable for the region of the participant’s primary residence until the age of 20 was entered to determine the main effects on their smelly food recall. In Step 3, an interaction term between marital status and the region of primary residence until the age of 20 was entered into the main effects model to test the moderating effect of the region of primary residence until the age of 20 on the association between marital status and smelly food recall. If the interaction term in Step 3 significantly improved the model, subsequent multiple comparisons of the interaction were performed. The comparisons utilized odds ratios calculated using the emmeans (estimated marginal means) library (Lenth, 2023; Searle et al., 1980) to estimate the moderating effect of the region of residence until age 20 on the association between marital status and smelly food recall.

3. Results

3.1 Results for the descriptive statistics

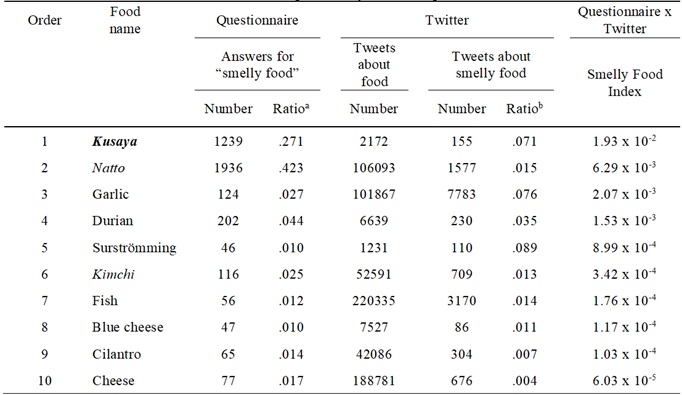

First, the top 10 foods were selected based on the response ratio of food name synonyms per valid responses to the descriptive questionnaire. Table 2 details the number and response ratio of food name synonyms in the descriptive questionnaire, the number of tweets containing food name synonyms, the number of co-occurrences of odor terms and food name synonyms, the co-occurrence ratio of odor terms and food name synonyms per food in tweets, and the Smelly Food Index, calculated by multiplying the response and co-occurrence rates. Natto (.423) had the highest response rate. Surströmming (.089) had the highest Twitter co-occurrence rate, and kusaya had the highest ranking in the Smelly Food Index (1.93 x 10-2, Table 2). Therefore, we selected kusaya as the target for subsequent analyses.

3.2 Main effect of region on recall of kusaya

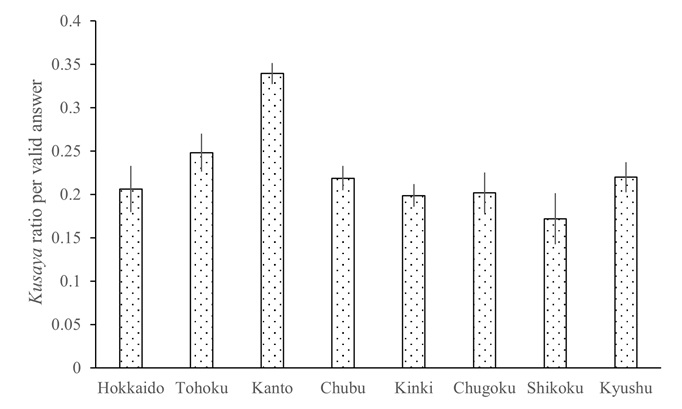

According to a study from 1967 (Simidu et al., 1967), the remote islands of Niijima and Oshima, which are included in the Kanto region, are the main production areas for kusaya, although the Kanto region itself is the main consumption area for kusaya. Furthermore, a study from 2011 (Fujii, 2011) reported that it is highly valued as a snack with alcohol, particularly in the Kanto region. In fact, the response rate for kusaya was highest among participants whose primary residence was in the Kanto region until the age of 20 (Figure 1).

Table 2. Top 10 smelly foods in Japan

Note. Bold: major smelly food. Participants who responded with “I do not know” (n = 347) and/or provided more than two responses when one was required (n = 6) were excluded from the top 10 calculation; however, they were included in subsequent analyses because their responses were not incorrect. aResponse ratio of food name synonyms per valid responses, bCo-occurrence ratio of odor terms and food name synonyms per food in tweets.

Figure 1. a: Kusaya response rate by region. The height of the bar indicates the ratio of kusaya responses per valid responses in each of the eight regions in the smelly food questionnaire. The straight line at the top of the bar represents the standard error. b: A map of Japan divided into eight regions to aid geographical understanding of each region.

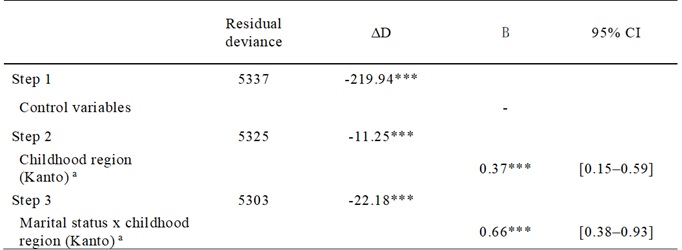

Therefore, we chose the Kanto region as the area to examine the effect of living there until the age of 20 on the recall of kusaya. Next, we analyzed the effect of the variable childhood region (Kanto); the Kanto region was used as the participant’s primary residence until the age of 20 on the questionnaire response regarding kusaya under the control variables. Specifically, we examined the effect of the variables based on the change in the degree of deviance (ΔD) when they were entered into the logistic regression model with the response of kusaya as the objective variable, as depicted in Table 3.

Table 3. Hierarchical multiple logistic regression analysis predicting recall of kusaya as a smelly food from attributes, region of childhood residence, and their interaction.

Note. ΔD: Difference in residual deviance, a: Participants who lived in the Kanto region until the age of 20.

***p < .001.

Control variables, including marital status and current region (Kanto)—the variable of the current address in the Kanto region—were input into the null model in Step 1. In Step 2, the deviation of the model was significantly reduced (ΔD = -11.25, p < .001) when childhood region (Kanto) was included in the Step 1 model. In addition, the main effect of childhood region (Kanto) on kusaya responses in the Step 2 model was significant in the positive direction (B = 0.37, z = 3.34, p < .001) (Table 3). Therefore, the participants’ residence in the Kanto region until the age of 20 increased their recall of kusaya as a smelly food in the questionnaire.

3.3 Interaction between marital status and childhood residence on recall of kusaya

We examined the moderating effect of living in the Kanto region until the age of 20 on the association between marital status and recall of kusaya as a smelly food using the interaction term entered into a hierarchical multiple regression analysis. We tested the model in Step 3 by adding an interaction term between childhood region (Kanto) and marital status to the model in Step 2, comprising control variables and childhood region (Kanto) until the age of 20 (Table 3). As a result, the degree of deviance in Step 3 in the model was significantly improved (ΔD = -22.18, p < .001) from Step 2, and the coefficient of the interaction was also statistically significant (B = 0.66, z = 4.70, p < .001) (Table 3). Therefore, multiple comparisons were performed using the interaction term between childhood region (Kanto) and marital status in the Step 3 model (Table 3).

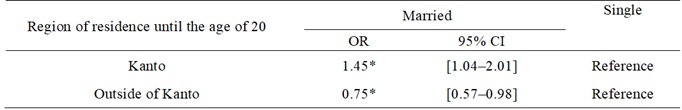

The results are presented in Table 4. These findings demonstrate that married participants who lived primarily in the Kanto region until the age of 20 were more likely (OR = 1.45, 95% CI [1.04–2.01]) to recall kusaya compared to the unmarried participants. Conversely, married participants who lived primarily outside the Kanto region until the age of 20 were less likely (OR = 0.75, 95% CI [0.57–0.98]) to recall kusaya than unmarried participants.

Table 4. Moderating effects, by marital status, of living in the Kanto region up to age 20 on changes in the probability of naming kusaya when asked to name a smelly food.

Note. Results are averaged over the levels of other attributes using the emmeans library in R (Lenth, 2023). The confidence level is 0.95. Intervals are back-transformed from the log odds ratio scale. Tests are performed on the log odds ratio scale. Confidence intervals and p-values are adjusted for four multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction. We also analyzed the moderating effect of marital status on the relationship between recall of kusaya and residence in the Kanto region until age 20; these results are not shown.

*p < .05.

4. Discussion

In considering the preservation of smelly traditional foods in communities, we hypothesized that residence in a region in which smelly food is produced and/or consumed during childhood would help people remember—and later recall—information about the smelly food, including its odor. This hypothesis is based on the results of previous studies, such as the integrated conceptual model of food choice (Chen & Antonelli, 2020) and the influence of food experiences through fetal (Faas et al., 2000, 2015; Hepper, 1995; Hepper et al., 2013; Mennella et al., 2001; Schaal et al., 2000), infant (Hausner et al., 2010; Mennella et al., 2001; Mennella & Beauchamp, 1993, 1999), and juvenile (Loth et al., 2016; Rodenburg et al., 2012; Unusan, 2006; Wadhera et al., 2015) life on future food choices, leading us to consider the possibility that region may influence an individual’s memory and recall of foods through family.

Furthermore, we examined the effect of marital status on smelly food recall. First, some participants who had experienced traditional smelly foods as children would remember them, either consciously or subconsciously. Additionally, we assumed that the memory of these foods would be recalled and reinforced by subsequent reconsolidation (Forcato et al., 2011), even if the participants were encouraged to eat these smelly foods by their families or if they tried to avoid these foods in consideration of the new family’s sense of smell. Finally, we hypothesized that marriage would positively affect the current recall of the smelly food by participants who experienced this food as children. However, it is difficult for participants to verbalize memories of experiences from the fetal stage to early childhood (Bauer, 2015). Therefore, we constructed a hypothesis by substituting memories of smelly food experiences up to the age of 20 with the residential region until the age of 20.

Traditional smelly food and the region of its production and/or consumption were selected to test these hypotheses. We selected kusaya as a representative traditional smelly food in Japan, with the Kanto region identified as the primary area for its consumption and production. Kusaya was ranked first in the Smelly Food Index, but it ranked second in the response rate for the descriptive questionnaire (Table 2). Natto topped the list in the descriptive questionnaire on smelly food (Table 2). One reason natto is so easy to recall is its widespread production and availability across Japan, making it easily accessible to people nationwide. However, unlike kusaya, it is difficult to identify the production and consumption region of natto. Therefore, even if the foods in this study had been selected using a descriptive questionnaire, kusaya would probably have been chosen instead of natto.

Hierarchical regression analysis demonstrated that living in the Kanto region until the age of 20 had a positive effect on recalling kusaya as a smelly food, even after controlling for the influence of current address (Table 3). This finding confirms Hypothesis I. Notably, while kusaya is a highly valued snack that accompanies alcoholic beverages (Fujii, 2011; Nakazato et al., 1995), it may seem surprising that the recall of kusaya is influenced by the participants’ childhood residence, given that drinking alcohol is prohibited in Japan until the age of 20. Although minors might not have many opportunities to eat kusaya, the strong odor emitted by this food when roasted before consumption can spread throughout the house. Therefore, the process of cooking kusaya may transmit the smell of the food to minors in the family. In addition, flying fish, which is one of the main ingredients of kusaya, was mentioned in a nineteenth-century book as being included in a celebration meal for a baby’s safe delivery (Iijima, 2014); even today, a web page for a kusaya shop (Osada Shōten, 2000) continues the legend that flying fish improves the milk supply of nursing mothers. It is possible that nursing mothers who had heard this legend had kusaya made from flying fish, allowing the smell to be passed on to their infants through breast milk. Thus, the participants’ residence in the Kanto region when they were minors may have increased the likelihood of them experiencing the smell of kusaya. However, these ideas are merely speculative. Furthermore, although we controlled for 17 variables in hierarchical multiple regression analysis, including alcohol consumption and current region of residence, these represent only a small portion of the respondents’ experiences affecting memory. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that the effect of residing in the Kanto region until age 20 is confounded. To eliminate the influence of post-adult experiences, an analysis limited to the minor years would be necessary. However, since all participants in this study were adults, such an analysis could not be performed.

In the interaction analysis, among participants who lived in the Kanto region until age 20, married individuals recalled kusaya more readily than single individuals. Conversely, among participants who lived outside the Kanto region until age 20, married individuals recalled kusaya less readily than single individuals (Table 4). This may be because the influence received from the region up to age 20 created differences in the frequency of opportunities to eat kusaya after marriage between those who lived in the Kanto region until age 20 and those who lived outside the Kanto region until age 20. Alternatively, due to influences received from their region until age 20, married individuals who resided in the Kanto region until age 20 may have had increased opportunities to recall memories of kusaya, while married individuals who resided outside the Kanto region until age 20 may have had increased opportunities to recall memories of other smelly foods. Or, even if both groups had the same post-marriage opportunities to recall kusaya, the presence or absence of prior kusaya memories may have influenced the strengthening of those kusaya memories. Although many of these hypotheses remain speculative and have not been proven within this study, these results suggest that the region where participants lived during childhood may have influenced the formation of memories associated with odorous foods, and that such memories may have been reinforced by marriage.

This study sought to explain why smelly food is preserved in production and consumption areas by looking at the impact of memories from one’s childhood place of residence. First, we indicated the possibility of the effect of the place of residence up to the age of 20 on the recall of kusaya. In addition, the interaction between place of residence up to age 20 and marital status led us to speculate that marital status may have reinforced participants’ recall of kusaya. This study contributes to the literature on the preservation of smelly foods produced and consumed in limited regions by providing information to examine factors related to the inheritance of memories associated with such foods within communities.

4.1 Limitations

This study focused only on one food, kusaya. Therefore, we cannot claim that a generalization of this study’s findings would allow for direct application of the results to other smelly foods with regional characteristics.

This cross-sectional observational study explored the factors that influence the recall of smelly food but, we could not clarify causal relationships. The hypotheses were based on inference owing to the paucity of previous studies on the sustainability of smelly food in society. In particular, the effects of marital status on kusaya recall remain unclear.

This study hypothesized that participants who lived in the Kanto region until age 20 would experience memory reinforcement due to increased recall opportunities for kusaya after marriage. However, since it has not been proven that recall opportunities for kusaya increase after marriage, proving memory reinforcement is also difficult. What can be clearly stated is this fact: married individuals who resided in the Kanto region until age 20 are more likely to recall kusaya as a smelly food compared to single individuals, while married individuals who resided outside the Kanto region until age 20 are less likely to recall kusaya than single individuals. While it is clear that the influence of family and community in childhood is mediated through memory, we used the place of residence as a proxy variable for memory. In the Introduction, we cite prior research on food transmission within families. However, this study focused on the impact of the regional sociocultural environment on memory, rather than the direct influence of family (e.g., shared food experiences between parents and children, family eating habits). Therefore, the details of the transmission mechanism mediated by the family remain unclear.

Furthermore, while this study includes information on primary residence areas up to age 20, it does not contain data on regional mobility during that period. Additionally, information on post-marriage residence and residence at the time of first alcohol consumption is also missing. Social and cultural factors associated with marriage, such as the spouse’s region of origin, preferences, and post-marriage household eating habits, were also not measured. It cannot be ruled out that these factors influenced the recall of kusaya. Due to the inability to control for these confounding variables, it is impossible to determine whether the association between marital status and recall of kusaya is causal or merely an apparent correlation due to these unmeasured variables. Therefore, the interpretation of memory enhancement through marriage should be positioned solely as an exploratory hypothesis. We also did not collect information on participants’ family dietary habits or food experiences with smelly foods during childhood, nor did we record the images or specific contexts evoked when recalling kusaya. This lack of information also represents a limitation of this study. Future research should combine qualitative research using interviews with the whole family and quantitative research using questionnaires to clarify what happened to families before preschool age and after changes in marital status. This study focused on adults to more easily replicate the age, gender, and prefectural population ratios of the Japanese population, but future research will likely need to include participants below the legal drinking age.

Although this study asked participants to describe only one smelly food as a method to measure recall, this method may be limited because participants may have been able to recall foods that were not described. We asked participants to provide simple responses because we believed that weighing the strength of recall and accuracy of responses for each food item would be difficult if participants had multiple responses to several smelly foods (as many as they could recall).

We used a Smelly Food Index, a combination of a descriptive questionnaire and natural language processing of tweet data on Twitter, to select representative smelly foods found in Japan. Natural language processing of the tweet data was used to correct the results of the descriptive questionnaire, which may be sensitive to recall, using the association between odor and food in the text. Due to individual differences in olfaction and odor preferences, it was difficult to measure “smelly” accurately. Therefore, it was difficult to validate the Smelly Food Index. However, the superiority of the Smelly Food Index over the descriptive questionnaire may be proven in the future when both results are compared between a human population and experts.

5. Conclusions

We developed two hypotheses to explain the persistence of traditional smelly food based on the integrated conceptual model of food choice and the influence of the family on children’s food choices. The first hypothesis stated that memories of living in a production/consumption region for traditional smelly foods up to the age of 20 would increase the likelihood of recalling the relevant food as a smelly food. The second hypothesis posited that memories of traditional smelly foods gained by living in a production/consumption region for these foods up to the age of 20 would be reinforced after marriage. To test these hypotheses, we chose kusaya as the food and Kanto as the area of interest, using the region of residence by age 20 as a surrogate variable of memory. The results of the hierarchical logistic regression analysis demonstrated that living in the Kanto region until age 20 increased the likelihood of recalling kusaya as a smelly food and confirmed the positive moderating effect of marital status on the recall of kusaya. This study indicated that individuals residing in the Kanto region until age 20 recalled kusaya more readily, though the causal relationship remains unclear. The hypothesis that marriage reinforces memories of kusaya among those residing in the Kanto region until age 20 could not be fully substantiated and remains speculative. Although this study has limitations, the results have implications for researchers seeking to understand the reasons for the existence of smelly food and for producers who wish to ensure the long-term consumption of smelly food, both in terms of the subjects analyzed and the methods used.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M. and A.O.; methodology, Y.M.; software, Y.M. and A.I.; formal analysis, Y.M.; investigation, Y.M. and A.I.; resources, A.I.; data curation, Y.M. and A.I.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.M.; writing—review and editing, A.I. and A.O.; visualization, Y.M.; supervision, A.O.; project administration, Y.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by an internal research fund from BIPROGY, the company that employed the first author during the course of the study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Review Committee for Life Science Research in BIPROGY Inc. (ID: 2020-002, approved with conditions on March 24, 2020; conditions were removed on May 21, 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Before answering the questionnaire, participants read the instructions and indicated via a check box that they agreed with the information contained in the instructions. The purpose of the questionnaire was explained in the instructions, namely, that it was a survey of smelly food names to examine the relationship between the names of the listed foods and various attributes. The information to be collected, how the data would be used, precautions for answering the questionnaire, freedom to discontinue the questionnaire, and the e-mail address of the principal researcher were also included in the web-based instructions.

Data Availability Statement

Owing to the nature of this research, the participants of this study did not provide their consent for their data to be shared publicly; therefore, supporting data are not available.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Tsutomu Yamada (Technology Research & Innovation, BIPROGY Inc.) for providing us with the Twitter data he had collected. The original text, written in Japanese by the authors, was first translated using DeepL Pro (DeepL Pro, 2024) and checked for grammar using DeepL Write (DeepL Write, 2024). The output English text was checked and revised by the authors and then revised by a private language editing service to improve the text’s readability. The revised manuscript was submitted after a final review by the authors. The authors take full responsibility for the manuscript’s content.

Conflicts of Interest

The first author and the second author, at the time of conducting this research, were employed by BIPROGY, which provided funds through allocation to the company laboratory.

References

Atilika Inc. (2018). Kuromoji. https://www.atilika.com/ja/kuromoji/

Bauer, P. J. (2015). A complementary processes account of the development of childhood amnesia and a personal past. Psychological Review, 122(2), 204–231. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038939

Belleggia, L., Aquilanti, L., Ferrocino, I., Milanović, V., Garofalo, C., Clementi, F., Cocolin, L., Mozzon, M., Foligni, R., Haouet, M. N., Scuota, S., Framboas, M., & Osimani, A. (2020). Discovering microbiota and volatile compounds of surströmming, the traditional Swedish sour herring. Food Microbiology, 91, 103503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fm.2020.103503

Castro, J. B., Ramanathan, A., & Chennubhotla, C. S. (2013). Categorical dimensions of human odor descriptor space revealed by non-negative matrix factorization. PLoS ONE, 8(9), e73289. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073289

Chen, P. J., & Antonelli, M. (2020). Conceptual models of food choice: Influential factors related to foods, individual differences, and society. Foods, 9(12), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9121898

DeepL Pro. (2024). DeepL SE. https://www.deepl.com/pro/change-plan?cta=footer-pro#single

DeepL Write. (2024). DeepL SE. https://www.deepl.com/write

Dravnieks, A. (1985). Atlas of odor character profiles. In ASTM Committee E-18 on Sensory Evaluation of Materials and Products, Subcommittee E-18.04.01 on Odor Profiling (p. 354). ASTM. http://www.astm.org/DIGITAL_LIBRARY/MNL/SOURCE_PAGES/DS61.htm

Esumi, Y. (2000). Mikaku kanjusei to shoku shūkan oyobi shokushikō to no kanrensei [Relationship between the taste perception, the dietary habits and the food preference]. Shimane Joshi Tankidaigaku Kiyou [Bulletin of Shimane Women’s Junior College], 38, 63–71.

Faas, A. E., March, S. M., Moya, P. R., & Molina, J. C. (2015). Alcohol odor elicits appetitive facial expressions in human neonates prenatally exposed to the drug. Physiology & Behavior, 148, 78–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.02.031

Faas, A. E., Spontón, E. D., Moya, P. R., & Molina, J. C. (2000). Differential responsiveness to alcohol odor in human neonates: Effects of maternal consumption during gestation. Alcohol, 22(1), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0741-8329(00)00103-8

Forcato, C., Rodríguez, M. L. C., & Pedreira, M. E. (2011). Repeated labilization-reconsolidation processes strengthen declarative memory in humans. PLOS ONE, 6(8), e23305. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0023305

Frank, R. A., & van der Klaauw, N. J. (1994). The contribution of chemosensory factors to individual differences in reported food preferences. Appetite, 22(2), 101–123. https://doi.org/10.1006/appe.1994.1011

Fujii, T. (1984). Funazushi. Dentō Shokuhin No Kenkyū [Quest for Traditional Food], 1, 29–30. https://doi.org/10.69331/questtraditionalfood.1.0_29

Fujii, T. (2011). Hakkō to fuhai wo wakeru mono—Kusaya, shiokara, funazushi ni tsuite [Differences between fermentation and putrefaction: Shiokara, kusaya and funazushi.]. Nippon Jōzōkyōkai Shi [Journal of the Brewing Society of Japan], 106(4), 174–182. https://doi.org/10.6013/jbrewsocjapan.106.174

Fukushima, H., Zhang, Y., Archbold, G., Ishikawa, R., Nader, K., & Kida, S. (2014). Enhancement of fear memory by retrieval through reconsolidation. eLife, 3, e02736. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.02736

Fuzihara, M., & Banba, R. (2014). Kodomo no kirai na shokumotsu to kokufuku he no shien: Daigakusei no yōjiki no kaisō ni yoru chōsa kenkyū [Foods that children hate and assistance from parent and teachers to overcome that problem in early childhood: A study of the college students’ reco. Kyōiku Gakubu Kiyō, Bunkyō Daigaku Kyōiku Gakubu [Annual Report of the Faculty of Education, Bunkyo University ], 48, 113–125.

GRAS Group, Inc. (2021). Weblio thesaurus. https://thesaurus.weblio.jp/

Hatanaka, Y., & Nunomi, M. (2019). Shōgakusei no tabemono no shikō to kenkō ninshiki: Shoku no manabi no arikata o saguru [Elementary school pupils’ food preference and health cognition: A consideration of dietary education]. Sapporo Gakuin Daigaku Jimbun Gakkai Kiyō [Journal of the Society of Humanities], 105, 183–196.

Hausner, H., Nicklaus, S., Issanchou, S., Mølgaard, C., & Møller, P. (2010). Breastfeeding facilitates acceptance of a novel dietary flavour compound. Clinical Nutrition, 29(1), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2009.11.007

Hepper, P. G. (1995). Human fetal “ Olfactory ” learning. International Journal of Prenatal and Perinatal Psychology and Medicine, 7(2), 147–151.

Hepper, P. G., Wells, D. L., Dornan, J. C., & Lynch, C. (2013). Long-term flavor recognition in humans with prenatal garlic experience. Developmental Psychobiology, 55(5), 568–574. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.21059

Higashiguchi, M. (2019). Ippan katei ni okeru shokuhin no shiyōjōkyō ni kansuru kenkyū [A study on the use of food in households]. Komazawa Joshi Daigaku Kenkyū Kiyō [The Faculty Journal of Komazawa Women’s University. Faculty of Human Health・Faculty of Nursing], 26, 25–36.

Honma, N., & Ishihara, K. (1996). Tōzai shokubunka no nihonkaigawa no setten ni kansuru kenkyū ( ix ): Nattō [Boundary Lines between Eastern and Western Food Cultures at Japan Sea Side of Japan (IX): Natto (Fermented Soybeans)]. Kenritsu Niigata Joshi Tanki Daigaku Kenkyū Kiyō [The Bulletin of Niigata Women’s College.], 33, 15–24.

Horio, T. (2012). Kirai na shokuhin no shikōhenka ni kansuru kenkyū [Study of preference change for disliked food]. Kenkyū Kiyō / (Kansai Kokusai Daigaku) (Hen) [The Bulletin of Kansai University of International Studies], 13, 115–123.

Horio, T. (2014). Yamitsuki shokuhin ni kansuru kenkyū [Study of addictive food]. Kenkyū Kiyō / (Kansai Kokusai Daigaku) (Hen) [The Bulletin of Kansai University of International Studies], 15, 95–101.

Iatropoulos, G., Herman, P., Lansner, A., Karlgren, J., Larsson, M., & Olofsson, J. K. (2018). The language of smell: Connecting linguistic and psychophysical properties of odor descriptors. Cognition, 178, 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2018.05.007

iBRIDGE Corporation. (2021). Freeasy. https://freeasy24.research-plus.net/

Iijima, Y. (2014). San’iku girei to zōtō “shinmotsu binran” wo chūshin ni [Gift-giving and rites of childbirth and child rearing: Focusing on shinmotsu benran]. Kozi : Tenri Daigaku Koukogaku Minzokugaku Kenkyuusitu Kiyou [Annual Bulletin of the Department of Archaeology and Folklore.], 18, 23–31.

Isahara, H., Bond, F., Uchimoto, K., Utiyama, M., & Kanzaki, K. (2008). Development of the Japanese WordNet. Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation ({LREC}’08), 2420–2423.

Keller, A., Zhuang, H., Chi, Q., Vosshall, L. B., & Matsunami, H. (2007). Genetic variation in a human odorant receptor alters odour perception. Nature, 449(7161), 468–472. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06162

Kobayashi, R., Matsuyama, M., Ohta, H., & Akari, W. (2016). Kōreisha no soshaku enka kinō to shokuhinshikō tono kanrensei [Relationship between oral function and food preferences among elderly Japanese]. Nihon Sesshoku Enka Rihabiritēshon Gakkai Zasshi [The Japanese Journal of Dysphagia Rehabilitation], 20(3), 132–139. https://doi.org/10.32136/jsdr.20.3_132

Kosugi, R., & Horio, T. (2005). Shokuhin no shikō to prop mikaku kanjusei no kankei [Relationship between food preference and taste sensitivity to PROP]. Eiyō Gaku Zasshi [The Japanese Journal of Nutrition and Dietetics], 63(5), 301–306. https://doi.org/10.5264/eiyogakuzashi.63.301

Kudo, T. (2005). CaboCha: Yet another Japanese dependency structure analyzer [Computer software]. http://taku910.github.io/cabocha/

Kudo, T. (2006). MeCab: Yet another part-of-speech and morphological analyzer [Computer software]. http://taku910.github.io/mecab/

Kudo, T., & Matsumoto, Y. (2002a). Chan kingu no dankai tekiyō ni yoru nihongo kakari uke kaiseki [Japanese dependency analysis using cascaded chunking]. Jōhōshori Gakkai Ronbunshi [Transactions of Information Processing Society of Japan], 43(6), 1834–1842.

Kudo, T., & Matsumoto, Y. (2002b). Japanese dependency analysis using cascaded chunking. CoNLL 2002: Proceedings of the 6th Conference on Natural Language Learning 2002 (COLING 2002 Post-Conference Workshops), 63–69.

Kudo, T., Yamamoto, K., & Matsumoto, Y. (2004). Applying Conditional Random Fields to Japanese Morphological Analysis. In D. Lin & D. Wu (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2004 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (pp. 230–237). Association for Computational Linguistics. https://aclanthology.org/W04-3230/

Kumar, R., Kaur, R., Auffarth, B., & Bhondekar, A. P. (2015). Understanding the odour spaces: A step towards solving olfactory stimulus-percept problem. PLoS ONE, 10(10), e0141263. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141263

Lenth, R. V. (2023). emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means (p. R package version 1.8.6) [Computer software]. https://cran.r-project.org/package=emmeans

Loth, K. A., MacLehose, R. F., Larson, N., Berge, J. M., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2016). Food availability, modeling and restriction: How are these different aspects of the family eating environment related to adolescent dietary intake? Appetite, 96, 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.08.026

Lüdecke, D., Ben-Shachar, M. S., Patil, I., Waggoner, P., & Makowski, D. (2021). performance: An R Package for Assessment, Comparison and Testing of Statistical Models. Journal of Open Source Software, 6(60), 3139. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.03139

Lunde, K., Egelandsdal, B., Skuterud, E., Mainland, J. D., Lea, T., Hersleth, M., & Matsunami, H. (2012). Genetic variation of an odorant receptor OR7D4 and sensory perception of cooked meat containing androstenone. PLoS ONE, 7(5), e35259. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035259

Mainland, J. D., Keller, A., Li, Y. R., Zhou, T., Trimmer, C., Snyder, L. L., Moberly, A. H., Adipietro, K. A., Liu, W. L. L., Zhuang, H., Zhan, S., Lee, S. S., Lin, A., & Matsunami, H. (2014). The missense of smell: Functional variability in the human odorant receptor repertoire. Nature Neuroscience, 17(1), 114–120. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3598

McRae, J. F., Jaeger, S. R., Bava, C. M., Beresford, M. K., Hunter, D., Jia, Y., Chheang, S. L., Jin, D., Peng, M., Gamble, J. C., Atkinson, K. R., Axten, L. G., Paisley, A. G., Williams, L., Tooman, L., Pineau, B., Rouse, S. A., & Newcomb, R. D. (2013). Identification of regions associated with variation in sensitivity to food-related odors in the human genome. Current Biology, 23(16), 1596–1600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2013.07.031

Mennella, J. A., & Beauchamp, G. K. (1993). The effects of repeated exposure to garlic-flavored milk on the nursling’s behavior. Pediatric Research, 34(6), 805–808. https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-199312000-00022

Mennella, J. A., & Beauchamp, G. K. (1999). Experience with a flavor in mother’s milk modifies the infant’s acceptance of flavored cereal. Developmental Psychobiology, 35(3), 197–203. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1098-2302(199911)35:3<197::aid-dev4>3.0.co;2-j

Mennella, J. A., Jagnow, C. P., & Beauchamp, G. K. (2001). Prenatal and postnatal flavor learning by human infants. Pediatrics, 107(6), E88. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.107.6.e88

Microsoft Corporation. (2018). Microsoft Excel [Computer software]. https://office.microsoft.com/excel

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan. (2015). Standard tables of food composition in Japan, 7th rev. Version. https://www.mext.go.jp/en/policy/science_technology/policy/title01/detail01/1374030.htm

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Japan. (2021). Basic resident ledger, population and households. https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00200241&tstat=000001039591&cycle=7&year=20210&month=0&tclass1=000001039601&stat_infid=000032110816&result_back=1&tclass2val=0

Mitsuhashi, T., Toda, S., & Hatae, K. (2008). Kōreisha no mikaku kanjusei to shokuhin shikō [Taste sensitivity and food preference of the elderly]. Nihon Chōri Kagakkaishi [Journal of Cookery Science of Japan], 41(4), 241–247. https://doi.org/10.11402/cookeryscience1995.41.4_241

Morquecho-Campos, P., de Graaf, K., & Boesveldt, S. (2020). Smelling our appetite? The influence of food odors on congruent appetite, food preferences and intake. Food Quality and Preference, 85, 103959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.103959

Nakazato, M., Saito, K., Moriyasu, T., Ishikawa, F., Fujinuma, K., Nishima, T., Tamura, Y., Sato, H., & Ogawa, T. (1995). Kusaya no kakō hin kara kenshutsu sa re ta fukihatsusei amin oyobi kihatsusei enki chisso no yurai ni tsui te [Source of putrefactive non-volatile amines and volatile basic nitrogen detected in kusaya products]. Shokuhin Eiseigaku Zasshi [Food Hygiene and Safety Science], 36(3), 393-399_1. https://doi.org/10.3358/shokueishi.36.393

Ogawa, A., & Nakazawa, H. (2018). Shokushikō no hattatsu ni kansuru kenkyū: Tanki daigakusei o taishō to shita ankēto chōsa [Development of food preference: A questionnaire survey of junior college students]. Naganoken Tankidaigaku Kiyo [Journal of Nagano Prefectural College], 72, 33–39.

Osada Shōten. (2000). Kusaya Shop “Osada Shōten.” http://kusaya.o.oo7.jp/8jyo/shop/tobiuo.htm

R Core Team. (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Computer software]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/

Ramaekers, M. G., Boesveldt, S., Gort, G., Lakemond, C. M. M., van Boekel, M. A. J. S., & Luning, P. A. (2014). Sensory-specific appetite is affected by actively smelled food odors and remains stable over time in normal-weight women. Journal of Nutrition, 144(8), 1314–1319. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.114.192567

Ramaekers, M. G., Boesveldt, S., Lakemond, C. M. M., Van Boekel, M. A. J. S., & Luning, P. A. (2014). Odors: Appetizing or satiating? Development of appetite during odor exposure over time. International Journal of Obesity, 38(5), 650–656. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.143

Rodenburg, G., Oenema, A., Kremers, S. P. J., & van de Mheen, D. (2012). Parental and child fruit consumption in the context of general parenting, parental education and ethnic background. Appetite, 58(1), 364–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2011.11.001

Sato, T., Hashimoto, T., & Okumura, M. (2017). Tango wakachigaki jisho mecab-ipadic-neologd no jissō to jōhōkensaku ni okeru kōkateki na shiyō hōhō no kentō [Implementation of a word segmentation dictionary called mecab-ipadic-NEologd and study on how to use it effectively for information retrieval]. Proceedings of the Twenty-Three Annual Meeting of the Association for Natural Language Processing.

Schaal, B., Marlier, L., & Soussignan, R. (2000). Human foetuses learn odours from their pregnant mother’s diet. Chemical Senses, 25(6), 729–737. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/25.6.729

Searle, S. R., Speed, F. M., & Milliken, G. A. (1980). Population marginal means in the linear model: An alternative to least squares means. The American Statistician, 34(4), 216–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/00031305.1980.10483031

Shimoda, M. (2011). Aji to kaori no kanren: Shokuhin kaihatsu no atarashii shiten [Relation between aroma and taste: A new viewpoint of food development]. Nihon Aji to Nioi Gakkaishi [The Japanese Journal of Taste and Smell Research], 18(2), 99–104. https://doi.org/10.18965/tasteandsmell.18.2_99

Simidu, W., Mochizuki, A., Simidu, U., & Aiso, K. (1967). Kusaya no kenkyū 1: Kusaya jiru no seibun oyobi kusaya jiru no kusaya no hinshitsu ni oyobosu eikyō [Studies of Kusaya-I: Chemical composition and preserving effect of the curing brine for Kusaya]. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi, 33(12), 1143–1146. https://doi.org/10.2331/suisan.33.1143

Skåra, T., Axelsson, L., Stefánsson, G., Ekstrand, B., & Hagen, H. (2015). Fermented and ripened fish products in the northern European countries. Journal of Ethnic Foods, 2(1), 18–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jef.2015.02.004

Spahn, J. M., Callahan, E. H., Spill, M. K., Wong, Y. P., Benjamin-Neelon, S. E., Birch, L., Black, M. M., Cook, J. T., Faith, M. S., Mennella, J. A., & Casavale, K. O. (2019). Influence of maternal diet on flavor transfer to amniotic fluid and breast milk and children’s responses: A systematic review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 109(Suppl. 7), 1003S–1026S. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqy240

Suzuki, Y., Matsuno, S., & Nakano, K. (2013). Hokkaidō iryō daigaku sei no shokumotsu shikō [Study of food preferences of the students in health sciences university of Hokkaido]. Hokkaidō Iryō Daigaku Ningen Kiso Kagaku Ronshū [Journal of Health Sciences University of Hokkaido: Liberal Arts and Sciences], 39, A1–A15.

Tateyama, K., Miyajima, A., & Shimizu, H. (2013). Jiheishōji no shoku shikō no jittai to henshoku he no taiō ni kansuru chōsa kenkyū [A study on the factors of food preferences and approaches for selective eating in children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD)]. Urakami Zaidan Kenkyū Hōkokusho [Urakami Foundation Memoirs], 20, 117–132.

The Apache Software Foundation. (2021). Apache Solr. https://solr.apache.org/

Toyomitsu, M., Ogawa, H., & Matsumoto, N. (2004). 3 sedai katei to 2 sedai katei ni okeru jakunensha to kōreisha no shoku shikō no hikaku [Comparison of preference for foods of younger generations and older person: Three generation family and two generation family.]. Nihon Shokuseikatsu Gakkaishi [Journal for the Integrated Study of Dietary Habits], 14(4), 289–297. https://doi.org/10.2740/jisdh.14.289

Unusan, N. (2006). University students’ food preference and practice now and during childhood. Food Quality and Preference, 17(5), 362–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2005.04.008

Wadhera, D., Capaldi Phillips, E. D., Wilkie, L. M., & Boggess, M. M. (2015). Perceived recollection of frequent exposure to foods in childhood is associated with adulthood liking. Appetite, 89, 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.01.011

Wysocki, C. J., & Beauchamp, G. K. (1984). Ability to smell androstenone is genetically determined. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 81(15), 4899–4902. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.81.15.4899

Zoon, H. F. A., de Graaf, C., & Boesveldt, S. (2016). Food odours direct specific appetite. Foods, 5(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods5010012

Relevant Articles

-

Exploring Undergraduate Students’ Transformative Learning Experiences through an eHealth Literacy Workshop in Japan

by Takafumi Tomura - 2026,1

VIEW -

Accuracy of peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO₂) at rest determined by a smart ring: A Study in Controlled Hypoxic Environments

by Yohei Takai - 2025,6

VIEW -

A Study on the Effectiveness of Glycerophosphocholine (α-GPC) as an e-Sports Supplement

by Yuki Kamioka - 2025,5

VIEW -

An attempt to realize digital transformation in local governments by utilizing the IT skills of information science students

by Edmund Soji Otabe - 2025,4

VIEW