Search for Articles

Impact of Three-Dimensional Multiple Object Tracking (3D-MOT) on Cognitive Performance and Brain Activity in Soccer Players

Journal Of Digital Life.2025, 5,S9;

Received:September 24, 2025 Revised:November 9, 2025 Accepted:February 9, 2026 Published:February 20, 2026

- Yoshiko Saito

- Graduate School of Life Science and Systems Engineering, Kyushu Institute of Technology, General Incorporated Association Behavior Assessment Systems Laboratory

- Hirohisa Isogai

- Department of Human Science, Kyushu Sangyo University, General Incorporated Association Behavior Assessment Systems Laboratory

- Kiyohisa Natsume

- Graduate School of Life Science and Systems Engineering, Kyushu Institute of Technology, General Incorporated Association Behavior Assessment Systems Laboratory

Correspondence: saitou@baslab.or.jp

Abstract

Previous studies on three-dimensional multiple object tracking (3D-MOT) training have primarily been conducted in controlled laboratory settings, with limited evidence on athletes’ self-training at home. This study examined the effects of home-based 3D-MOT training using the NeuroTracker X (NTX) application on cognitive performance and brain activity in 29 university soccer players. Participants in the NTX group demonstrated significant post-training improvements in NTX scores (p < .001) and 2-back task accuracy (p = .045), which indicated enhanced 3D-MOT ability, working memory, and attentional functions. Brain wave recordings during the 2-back task revealed a significant increase in alpha power (p < .001). This provided novel evidence that NTX self-training modulated brain activity associated with working memory and attentional control among athletes. These findings highlight the potential of combining NTX interventions with EEG assessments and suggest that NTX-based 3D-MOT self-training may be a practical tool for enhancing attentional aspects of cognitive function in athletes.

keywords:

1. Introduction

Three-dimensional multiple object tracking (3D-MOT) is a computerized cognitive training method designed to improve the ability to simultaneously track and monitor multiple moving objects in a dynamic 3D space. It is a useful tool for evaluating and improving cognitive function (Parsons et al., 2016). This 3D-MOT training approach has been utilized in various fields, including sports (Faubert, 2013; Romeas et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2025), education and learning (Che et al., 2023), dementia prevention and older adult care (Burgos-Morelos et al., 2025), and military, aviation, and professional training (Vartanian et al., 2016). Regarding its effects, Parsons et al. (2016) reported that it effectively improved cognitive functions, such as attention, visual processing speed, and working memory (WM). Clinically, it effectively improved attention in children with developmental disorders (Tullo et al., 2018). Assed et al. (2020) demonstrated that combining 3D-MOT training with memory training improved various cognitive functions, including attention, reaction time, visual processing speed, episodic memory, WM, and social cognition; furthermore, the effects were particularly pronounced in the 3D-MOT group.

3D-MOT training tools include Lumosity (Lumos Labs, USA) and CogniFit (CogniFit, USA) for adults, and NeuroTracker (NT; NeuroTracker Inc., Canada). Among these, NT is the most popular in the sports field and has been used in numerous intervention studies to provide scientific evidence in open-skill sports, such as soccer, basketball, and ice hockey (Acquin et al., 2024; Komarudin et al., 2021; Romeas et al., 2016; Tétreault et al., 2024). Open-skill sports require immediate judgment and adaptation in rapidly changing external environments with unpredictable opponents, balls, and situations. Although many studies have used NT, all have used stand-alone types, which have limitations in practical cases. These systems are expensive, can only be used at fixed locations, and must be shared among multiple users, which reduces efficiency. Therefore, NeuroTracker X (NTX; NeuroTracker Inc., Canada) was developed for practical use. It can be downloaded to an individual personal computer, which allows users to train anywhere and anytime. Furukado et al. (2024) used NTX to train professional baseball players for approximately five months and investigated the effects of MOT skill training on their batting performance. The results showed a 128% improvement in NTX scores after training, batting performance also improved, particularly regarding zone contact and swinging-strike rates, especially against breaking balls. However, they did not include a control group. Thus, no systematic studies have investigated changes in cognitive abilities or brain activity in athletes via individual NTX self-training.

Cognitive functions, such as WM and attention control, play a crucial role in athletic performance, particularly in open-skill sports that require rapid information processing and decision-making under time constraints (Voss et al., 2010). Although the efficacy of 3D-MOT training has been recently debated (Romeas et al., 2025; Vater et al., 2021), most studies have focused on behavioral outcomes; no research has investigated brain activity in athletes undergoing NTX training.

Brain waves (EEG) reflect brain activity. Electroencephalogram (EEG) devices are small, easy to install, and inexpensive to acquire and maintain. Hence, EEGs are easy to use for measurements in laboratories and in the field (Chikhi et al., 2022). EEG measures delta (1–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), beta (13–30 Hz), and gamma (30–50 Hz) waves. Theta waves are induced by WM, attention, and cognitive loads. Frontal theta waves are reliable markers of cognitive load (Chikhi et al., 2022; Riddle et al., 2021). Alpha waves are involved in high levels of attention and cognitive load (Chikhi et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2018). Beta waves are associated with concentration and cognitive control and are facilitated during task performance (Chikhi et al., 2022; Riddle et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2018). Gamma waves are essential for memory processes and contribute to the improvement of cognitive impairments (Kucewicz et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2022).

Previous research that combined 3D-MOT and EEG in healthy individuals, not athletes, reported improved attention, WM, and information processing speed, and changes in resting-state EEG after 3D-MOT training (Parsons et al., 2016). Furthermore, recent studies have demonstrated that real-time EEG neurofeedback during 3D-MOT training can enhance learning using NT (Parsons & Faubert, 2021) and employed alpha waves as the neurofeedback signal. Roy and Faubert (2022) analyzed brain activity across the three stages of a 3D-MOT task (identification, tracking, and recall), which indicated a within-task handoff from attention-dominant to WM-dominant processing when moving from tracking to recall. These studies have greatly contributed to elucidating the neural basis of cognitive functions and visualizing the effects of training. However, the effects of 3D-MOT training on behavioral performance and EEG activity in athletes remain insufficiently understood.

Therefore, we hypothesized that NTX self-training would improve 3D-MOT ability, enhance WM and attention function performance in athletes, and influence brain activity. We investigated the effects of spontaneous 3D-MOT training via NTX on the cognitive performance and brain activity of university soccer players.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

This study included 30 male students from the soccer team of K.S. University, a highly competitive team with a history of participating in national championships. All participants were regular class players. To minimize variability in soccer players’ skill levels, the team’s head coach and coaching staff assisted in assigning players to either the NTX training group (n = 15) or the control group (n = 15).

One participant in the control group was absent for the post-measurement; therefore, the final analysis included 15 and 14 participants in the NTX and control groups, respectively. Mean age was 19.9 ± 1.2 years in both groups, with no significant difference (p = .89). Mean soccer experience was 13.5 ± 2.2 and 12.6 ± 3.4 years in the NTX and control groups, respectively, with no significant difference (p = .41). All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision that did not interfere with the experiment. None had prior experience with 3D-MOT training, cognitive tasks, or EEG measurements. Prior to participation, the purpose and procedures of the study, as well as the handling of personal information, were explained in detail. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after they voluntarily agreed to participate.

2.2 Group Assignment

The head coach and coaching staff were asked to randomly assign players while considering key factors such as academic year (age) and playing position. This procedure ensured that individual characteristics did not become unevenly concentrated in either group while maintaining randomness. No intentional selection bias based on the performance level was introduced.

2.3 Protocol

To examine the effects of 3D-MOT training using NTX, a pre-post experimental design was employed. Both the NTX training and control groups completed the same cognitive tasks and EEG recordings before (pre) and after (post) the training. The pre- and post-experimental periods lasted approximately 10 days. Training for the NTX group began immediately after the pre-experimental period and ended at the onset of the post-experimental period. The procedure was as follows: first, EEG devices were attached to the participants; subsequent cognitive tasks, which included the 3D-MOT and n-back tasks, were performed. EEG was measured during the n-back task. The NTX training group underwent 30 NTX training sessions over a 9-week period at home in addition to their usual activities. The control group did not undergo any specific training and continued their usual activities. The pre- and post-experimental days are referred to as Pre and Post days, respectively.

2.4 NTX Training

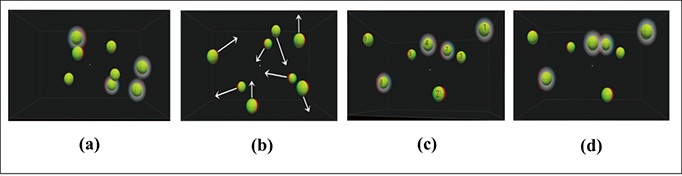

Participants in the NTX group were asked to bring their own computers on the Pre day and install the NTX software (https://neurotracker.net/download-installer/). They were provided with instructions on how to use the software and perform training so they could begin at home. Participants were asked to sit at a distance of approximately 40 cm from their eyes to the PC screen, following the NTX manual. They were lent 3D anaglyph glasses and wore them during NTX training. These glasses enabled them to view 3D images. Participants completed 30 NTX sessions using their own PCs, performing 1–2 sessions per day at a frequency of 2–3 days per week. Each session comprised 20 trials and lasted approximately 6 min. One trial comprised steps (a) to (d), as shown in Fig. 1. First, eight yellow balls appeared on the screen, and four of them—the targets to be tracked—appeared in a slightly larger, highlighted form for two seconds (Identification phase; Fig. 1a). Subsequently, the balls moved for 8 s along unpredictable linear paths in a three-dimensional space perceived through the 3D glasses (Tracking phase; Fig. 1b). Within this depth-rich virtual space, the balls travelled forward/backward and upward/downward, occasionally bouncing off the walls or colliding with each other, creating highly unpredictable motion patterns that participants had to track. After the balls stopped, numbers were displayed on them, and the participant had to select the numbers of the four target balls using either a touchscreen or keyboard, depending on each PC (Recall phase; Fig. 1c). Finally, the correct target balls were highlighted (Feedback phase; Fig. 1d). If the participants’ choices were correct, the moving speed of the balls increased in the next trial; if there was a mistake with at least one ball, the speed decreased. After approximately three seconds, the next trial started. The speed varied via a 1-up/1-down staircase method (Levitt, 1971) to determine the ball speed threshold. The ball speed threshold was a numerical value that indicated the maximum speed of the balls at which a participant could accurately track the targets during the trials. Each session included 20 trials. The NTX score was displayed at the end, reflecting the ball speed threshold (Parsons et al., 2016). The higher the NTX score, the faster a participant was able to track the target balls. NTX scores for each session were shared between the participant and the experimenter, and other participants could not view the records.

One trial included the steps from (a) to (d). Details are described in the text.

2.5 Cognitive Tasks

2.5.1 3D-MOT Task

Experiments were conducted at the university’s Sport Psychology Laboratory during Pre and Post days. All participants visited the laboratory to participate.

The NTX score reflected 3D-MOT skills (Isogai, 2023); hence, we used this score as an evaluation metric for the skills. Each participant completed one NTX session via a 15.5-inch notebook computer (NEC Endeavor SE-09079, Japan) as a cognitive task. Participants wore 3D anaglyph glasses and sat at a distance of approximately 40 cm from the screen, similar to during training. On the Pre day, responses were uniformly made using the keyboard, with 2–3 practice trials conducted to explain the task, followed by the main measurement task.

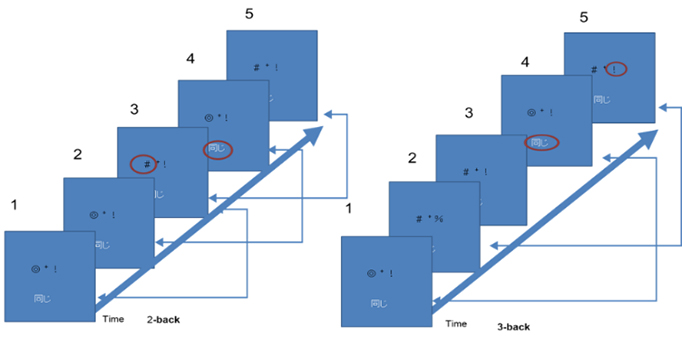

2.5.2 Working Memory Task

The n-back task is one of the most common experimental paradigms used in WM studies. Recently, variations of the n-back procedure (Owen et al., 2005) have been widely adopted. We used the non-verbal WM task shown in Fig. 2. This task was a modified version of the n-back task (n = two and three) (Park et al., 2013). It was conducted on a 15.5-inch notebook computer (NEC Endeavor SE-09079, Japan). Fig. 2 presents the time sequence of the computer screen for the 2- and 3-back tasks. We mainly explained the 2-back task. When the trial began, at the starting cue, a black cross appeared at the center of the screen for one second. Subsequently, a pair of symbols appeared on the left and right sides of the cross. Each pair of symbols was presented on the screen for 1–5 s. Participants were asked to click on the “different” symbol via the PC mouse within five seconds if the symbols on the previous two screens were different (Fig. 2, left) from the current ones. If the two symbols were the same, the participant clicked the “same” (“同じ” in Japanese) button at the bottom of the screen (Fig. 2, left). The positions of the symbols did not change across three continuous screens. Participants completed 20 trials, after which their accuracy rate and average reaction time were recorded. For the 3-back task, participants compared a pair of symbols with a pair from the previous three screens; other points were the same as those in the 2-back task. On the Pre day, we conducted 2–3 practice trials before the measurement task. The custom-made task program was developed using Unity (Unity Technologies, USA).

Numbers indicate the order of the presented screen. The participant compared the two screens indicated by both arrows. Symbols included the following 18 symbols:〇,△,□,!, #, &,¥,★,→,←,↓,↑,※,◎,♪, @,◇,▽.

2.6 EEG Measurement

EEG signals were recorded to investigate the effects of NTX-based 3D-MOT self-training on brain activity. EEG was measured from approximately 10 s before the 2- and 3-back tasks until after the task on both days. It was measured at the Fz site of the brain based on the International 10/20 system. A reference electrode was placed on the mastoid and a ground electrode on the FPz site. EEG was measured at the Fz electrode site because frontal midline activity, particularly at Fz, is considered a stable and sensitive indicator of WM load and attentional control (e.g., Gevins & Smith, 2000). Measurement was performed using the Intercross-415 (Intercross Co., Ltd., Japan). Sampling frequency was set to 1000 Hz. Analysis was performed using MATLAB R2020b (MathWorks, USA) with EEGLAB (https://sccn.ucsd.edu/eeglab/index.php). After blink artifacts were excluded via the ICA program, short-time fast Fourier transformation analysis was performed. Baseline correction was performed using the power values for 0.5 s prior to task onset. Time-average power values during the task were calculated for each frequency band: θ (4–8 Hz), α (8–13 Hz), β (14–29 Hz), and γ (30–40 Hz).

2.7 Statistical Analysis

A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was performed for the results of each cognitive task and EEG power, with the factors of measurement timing (Pre day × Post day) and group (NTX group × control group). Due to PC trouble, some data from the NTX and control groups in the 2-back task at the Post day and the 3-back task at the Pre day were lost, respectively. Hence, data from 14 participants in the NTX and control groups in the 2-back task at the Post day, and 15 in the NTX group and 13 in the control group in the 3-back task at the Pre day were analyzed. Based on the statistical analysis results, a simple main-effect test was conducted when an interaction was significant. Figures were presented only when a significant interaction was observed. A p-value of <5% was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the open source software JASP version 0.19.2 (Netherlands, https://jasp-stats.org/download/).

3. Results

3.1 NTX Training

In the 9-week NTX self-training, the NTX group completed approximately 29 sessions (28.5 ± 3.8, n = 15). Of the 15 participants, 12 completed 30 sessions as requested, whereas three did not achieve the goal. The average NTX score for the first three sessions was 1.8 ± 0.4, and the score for the last three sessions was 2.3 ± 0.3, representing approximately 128% of the baseline score by self-training.

3.2 Cognitive Tasks

3.2.1 3D-MOT Task

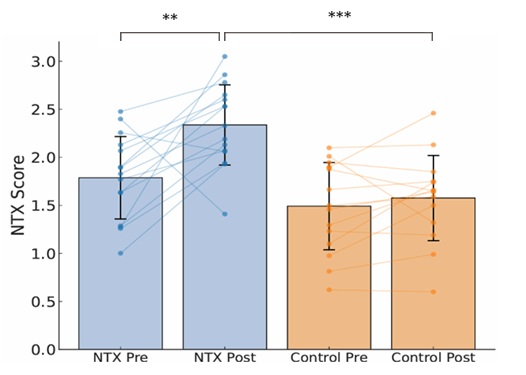

A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted on the NTX scores with the factors of measurement timing and group. Results revealed a significant interaction (F(1, 27) = 5.52, p = .026, η²ₚ = .170); therefore, a simple main effect test was conducted. Regarding the measurement timing factor, the NTX group demonstrated significantly higher scores at Post (M = 2.34, SD = .43) than at Pre (M = 1.79, SD = .44) (F(1, 27) = 12.26, p = .004). Conversely, the control group demonstrated no significant difference between Pre (M = 1.46, SD = .48) and Post (M = 1.58, SD = .46) (F(1, 27) = 1.43, p = .247). Regarding group factors, no significant difference was observed between the NTX (M = 1.79, SD = .44) and control groups (M = 1.46, SD = .48) at Pre (F(1, 27) = 3.61, p = .068). However, at Post, the NTX score in the NTX group (M = 2.34, SD = .43) was significantly higher than that in the control group (M = 1.58, SD = .46) (F(1, 27) = 21.09, p < .001) (Fig. 3).

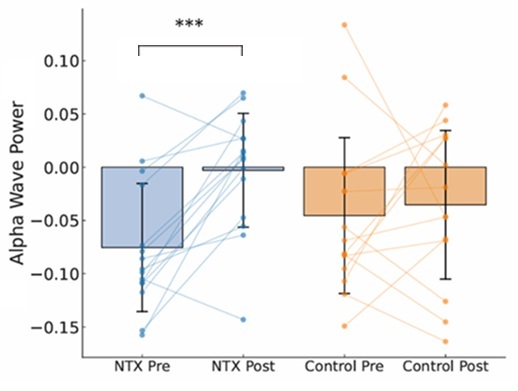

In this and subsequent figures, the blue and orange bars indicate the mean values for the NTX and control groups, respectively. Error bars indicate the standard deviation. Blue and orange dots represent individual data points, and lines connecting each point indicate individual changes between Pre and Post.

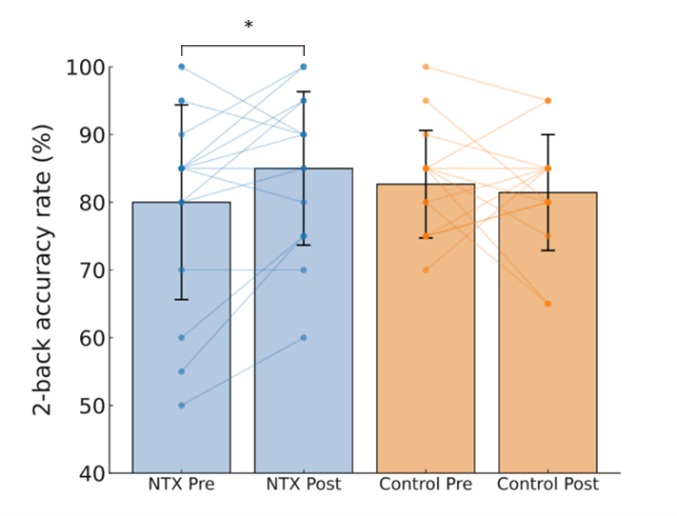

3.2.2 Working Memory Task

A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to examine the accuracy rate and reaction time for the 2-back and 3-back tasks. The results revealed a significant interaction in the accuracy rate for the 2-back task (F(1, 26) = 4.43, p = .045, η²ₚ = .145). Therefore, a simple main effect analysis was performed. Regarding the measurement timing factor, the NTX group showed significantly higher accuracy at post-test (M = 85.00, SD = 11.77) than at pre-test (M = 78.93, SD = 14.83) (F(1, 26) = 6.34, p = .026). However, no significant difference was observed in the control group between Pre (M = 83.21, SD = 8.23) and Post (M = 81.43, SD = 8.86) (F(1, 26) = 0.39, p = .542). For the group factor, no significant differences were observed between the two groups at either Pre (F(1, 26) = 0.89, p = .353) or Post (F(1, 26) = 0.82, p = .373) (Fig. 4). Furthermore, no significant interaction was observed in the accuracy rate in the 3-back task.

Regarding reaction time, no significant interactions were observed in either the 2-back or 3-back tasks. However, a significant main effect of measurement timing was observed in both tasks; participants responded faster at Post than at Pre (2-back: F(1, 26) = 4.97, p = .035, η²ₚ = .160; 3-back: F(1, 26) = 7.23, p = .012, η²ₚ = .218). The shortened reaction time at Post in both groups could be due to the practice effect of task performance.

3.3 EEG Measurement

A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted on the EEG power at the Fz site during the 2- and 3-task, with measurement timing and group as factors. Results revealed a significant interaction in the alpha band during the 2-back task (F(1, 27) = 4.33, p = .047, η²ₚ = .138); therefore, simple main effects were examined. In the NTX group, alpha power was significantly higher at Post (M = −.003, SD = .060) than at Pre (M = −.075, SD = .060) (F(1, 27) = 20.76, p < .001). However, no significant difference was observed between Pre (M = −.047, SD = .078) and Post (M = −.035, SD = .072) (F(1, 27) = 0.22, p = .646) in the control group. Since the task-related alpha power was baseline-corrected, the values were negative when alpha was suppressed relative to the baseline. For the group factor, no significant between-group differences were observed at either Pre or Post. Furthermore, no significant interactions were observed in the 2-back task for the frequency bands, except the alpha band. During the 3-back task, no interactions were observed in any frequency band at the Fz.

4. Discussion

A previous study asked participants to visit the laboratory for 3D-MOT training via NT. In contrast, NTX allowed users to train independently anytime and anywhere. While this usability is a major advantage, it also carries the risk that participants may skip sessions without supervision. Therefore, to support the feasibility of a self-directed training environment, we implemented minimal monitoring using a management interface and provided brief reminder-style verbal check-ins. These procedures were not intended to enhance motivation or performance, but to prevent large deviations in training adherence. Participants completed 28.5 ± 3.8 NTX sessions over nine weeks (approximately two months).

Furukado et al. (2024) trained 12 professional baseball players for approximately five months using NTX to examine the impact of MOT skill training on batting performance; however, they did not include a control group. In comparison, the present study included a control group, thereby increasing the internal validity of the findings regarding NTX-based 3D-MOT training in university athletes.

4.1 Effects of NTX Training on Cognitive Function

4.1.1 3D-MOT Ability

Furukado et al. (2019) reported that when university baseball players underwent 12 sessions of training over three weeks via NT, the NT training group demonstrated significant improvements in scores and a positive effect on 3D-MOT ability. Participants underwent controlled training in the laboratory. In our study, which used NTX self-training with university soccer players, a significant interaction effect was observed (measurement timing × group) (Fig. 3); the improvement rate of NTX scores was 130% in the NTX group compared with 107% in the control group. This was similar to previous results obtained with self-training in participants’ usual environments. Hence, a definite improvement in 3D-MOT ability could be achieved in approximately 30 sessions, even in self-training outside a controlled laboratory environment.

4.1.2 Working Memory Task

We investigated whether NTX training influenced cognitive abilities beyond 3D-MOT performance by examining its effects on the 2-back and 3-back tasks in university soccer players. The n-back task is widely used to assess WM function (Owen et al., 2005). In this task, participants compare the current stimulus with the stimulus presented n steps earlier, requiring online monitoring, updating of stored information, sustained attention, and attentional switching between stimuli (Kane et al., 2007). Since the n-back task places considerable demands on several key WM processes (Owen et al., 2005), it shares conceptual similarities with the cognitive processes engaged in during NTX training, which consists of four sequential phases: recognition, tracking, recall, and feedback. Roy and Faubert (2022) have demonstrated that these phases involve a dynamic handover between attention and WM, suggesting that 3D-MOT training can influence both domains.

In the present study, a significant interaction was observed in the accuracy of the 2-back task, with performance improving only in the NTX group (Fig. 4). These results indicated that NTX training enhanced WM and attentional regulation under moderate task demands. However, no significant improvement was observed in the 3-back task. Pre-training accuracy was lower for the 3-back task (73.3%) than for the 2-back task (81.3%), indicating that the 3-back task imposed a higher cognitive load. Previous research has shown that prefrontal activation decreases when task demands escalate from 2-back to 3-back (Callicott et al., 1999), suggesting increased neural inefficiency under a heavier cognitive load.

Together, these findings suggest that NTX training can be transferred to cognitive tasks with moderate WM demands, whereas transfer to more complex WM processing appears to be limited within the current intervention framework. NTX uses a 1-up/1-down adaptive staircase procedure (Levitt, 1971), which increases task speed after correct responses and decreases task speed after errors, thereby maintaining difficulty at an individually appropriate level. Rather than implying that the protocol was inherently designed to enhance maximal WM capacity, it is more appropriate to interpret that the adaptive load adjustment may have aligned optimally with the cognitive demands of the 2-back task. This alignment may support the transfer of attentional regulation and short-term information maintenance. By contrast, the substantially higher cognitive load of the 3-back task may have exceeded the range in which transfer effects could have occurred under the present training conditions.

4.2 Effects of NTX Training on Brain Activity

We compared the power of brain waves that reflected brain activity during 2/3-back tasks before and after NTX training. Consequently, a significant increase in alpha wave power was observed during the 2-back task in the NTX group after training (Fig. 5). Increased alpha waves have been associated with inhibitory functions that protect against external interference (Toscani et al., 2010; Tuladhar et al., 2007; Webster & Ro, 2020).

The pre-training accuracy rate of the 2-back task was 81.3%, indicating that the difficulty level was close to optimal for the participants. This task required participants to remember the screen two steps earlier while focusing attention on holding the screen one step back, which involved relatively short-term memory and repeated attention. Thus, the observed increase in alpha waves may be associated with the “gate function” (Jensen & Mazaheri, 2010), which prioritizes necessary information and suppresses unnecessary information. Furthermore, an increase in alpha waves may reflect the suppression of neural activity and selective allocation of cognitive resources, which may indicate a state in which unnecessary information for the task is effectively suppressed (Klimesch, 2012; Payne & Sekuler, 2014). This change suggests improved neural efficiency, selective control of attentional resources, and reduced cognitive load through training. The pre-training accuracy of the 3-back task was 73.3%, reflecting a higher cognitive load than the 2-back task; when tasks are perceived as difficult and demanding, the brain must allocate more resources to the task, which can result in the suppression of the alpha band in the frontal region (Jensen & Mazaheri, 2010).

Although the frontal theta activity is widely regarded as a reliable index of cognitive load, no significant interaction was observed in the theta band in the present study. Since NTX is designed to optimize attentional regulation through its adaptive speed-based algorithm, it is more likely to enhance attentional processes rather than directly increasing WM capacity. This interpretation aligns with the behavioral findings that showed improvement only in the 2-back task and not in the 3-back task.

In contrast, alpha oscillations are strongly associated with sustained attention and attentional resource allocation. Therefore, the significant interaction observed in alpha power likely reflects the preferential modulation of attentional control mechanisms induced by NTX training.

5. Limitations and Future Directions

The primary methodological limitation of the present study is related to the characteristics of the NTX training protocol. The results indicate that the protocol effectively enhanced attentional control; however, improvements in higher-level WM processes were not observed during the intervention period. This suggests that the current NTX configuration may not impose sufficient memory-related cognitive load to induce measurable gains in WM capacity. To target WM enhancement more directly, future implementations of NTX may require increased task complexity; for example, by increasing the number of tracked objects or incorporating dual-task paradigms that simultaneously demand attention and memory retention. Such modifications may better challenge the memory manipulation processes necessary for improvements in higher-order WM functioning.

Furthermore, the development of more advanced adaptive training environments, including AI-based feedback systems capable of dynamically monitoring progress and adjusting task difficulty, may contribute to establishing a fully autonomous training model that effectively supports attentional enhancement and WM improvement.

6. Conclusion

This study investigated the effects of NTX-based 3D-MOT self-training on the cognitive function and brain activity of university soccer players. NTX is a personal, autonomously performed training tool that differs from the laboratory-based standalone 3D-MOT systems used in previous research. Consistent with earlier findings, NTX performance improved significantly after approximately 30 training sessions. A significant interaction was observed in the 2-back task, with the accuracy increasing only in the NTX group. This finding indicates that NTX training successfully enhanced attentional control and short-term information updating—cognitive processes that are closely aligned with the adaptive attentional demands imposed by the NTX protocol. In contrast, no improvement was observed in the more demanding 3-back task, suggesting that the present NTX training configuration was insufficient to induce measurable gains in higher-level WM manipulation.

Neurophysiological results supported this interpretation; alpha-band power, an index of sustained attention and inhibitory control, significantly increased during the 2-back task following NTX training, whereas frontal theta activity, typically associated with WM load, did not show any interaction effects. Together, these findings indicate that the NTX protocol primarily strengthened attentional regulation rather than the higher-order WM capacity.

In addition to these laboratory outcomes, our findings also have important implications for real-world soccer cognition. Effective soccer performance frequently requires players to maintain the spatial positions of multiple teammates and opponents, while making rapid decisions under pressure. These situations rely on both WM and attentional control. Based on the present results, the NTX training protocol appears to have selectively enhanced attentional processes, as evidenced by improvements in the 2-back task and alpha-band modulation. Therefore, the attentional gains induced by NTX training may contribute to reduced passing errors and improved decision-making accuracy during gameplay, even though enhancements in more complex WM processes were not evident under the current training conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y. S.; methodology, Y. S., H. I., and K. N.; software, H. I. and K. N.; validation, Y. S.; formal analysis, Y. S. and K. N.; investigation, Y. S. and H. I.; resources, Y. S. and K. N.; data curation, Y. S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y. S.; writing—review and editing, Y. S. and K. N.; visualization, Y. S.; supervision, K. N.; project administration, Y. S. and K. N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and its future amendments and was approved by the Kyushu Institute of Technology Human Experimentation Committee (protocol #23-01).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the head coach and coaching staff of K.S. University for their cooperation in recruiting participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Acquin, J. M., Desjardins, Y., Deschamps, A., Fallu, É., Fait, P., & Corbin-Berrigan, L. A. (2024). Impact of biological sex, concussion history and sport on baseline NeuroTracker performance in university varsity athletes. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 6, 1372350. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2024.1372350

Assed, M. M., Rocca, C. C. D. A., Garcia, Y. M., Khafif, T. C., Belizario, G. O., Toschi-Dias, E., & Serafim, A. D. P. (2020). Memory training combined with 3D visuospatial stimulus improves cognitive performance in the elderly: pilot study. Dementia & Neuropsychologia, 14(03), 290-299. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-57642020dn14-030010

Burgos-Morelos, L. P., Rivera-Sánchez, J. D. J., Santana-Vargas, Á. D., Arreola-Mora, C., Chávez-Negrete, A., Lugo, J. E., … & Pérez-Pacheco, A. (2025). Effect of 3D-MOT training on the execution of manual dexterity skills in a population of older adults with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult, 32(2), 328-337. https://doi.org/10.1080/23279095.2023.2169884

Callicott, J. H., Mattay, V. S., Bertolino, A., Finn, K., Coppola, R., Frank, J. A., … & Weinberger, D. R. (1999). Physiological characteristics of capacity constraints in working memory as revealed by functional MRI. Cerebral cortex, 9(1), 20-26. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/9.1.20

Che, X., Zhang, Y., Lin, J., Zhang, K., Yao, W., Lan, J., & Li, J. (2023). Two-dimensional and three-dimensional multiple object tracking learning performance in adolescent female soccer players: The role of flow experience reflected by heart rate variability. Physiology & Behavior, 258, 114009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2022.114009

Chikhi, S., Matton, N., & Blanchet, S. (2022). EEG power spectral measures of cognitive workload: A meta‐analysis. Psychophysiology, 59(6), e14009. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.14009

Ericsson, K. A. (2006). The influence of experience and deliberate practice on the development of superior expert performance. The Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance, 38(685-705), 2-2. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511816796.001

Faubert, J. (2013). Professional athletes have extraordinary skills for rapidly learning complex and neutral dynamic visual scenes.Scientific reports, 3(1), 1154. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01154

Furukado, R., Akiyama, D., Sakuma, T., Shinriki, R., Hagiwara, G., & Isogai, H. (2019). Training Effects of Multiple Target Tracking Skills and Visual Search Strategies. Ergonomics, 55(2), 33-39. https://doi.org/10.5100/jje.55.33

Furukado, R., Saito, Y., Ichikawa, T., Morikawa, K., Enokida, D., & Isogai, H. (2024). Transferability of multiple object tracking skill training to professional baseball players’ hitting performance. Journal of Digital Life, 4(SpecialIssue). https://doi.org/10.51015/jdl.2024.4.S5

Gevins, A., & Smith, M. E. (2000). Neurophysiological measures of working memory and individual differences in cognitive ability and cognitive style. Cerebral cortex, 10(9), 829-839.

Hatfield, B. D., Haufler, A. J., Hung, T. M., & Spalding, T. W. (2004). Electroencephalographic studies of skilled psychomotor performance. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology, 21(3), 144-156. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004691-200405000-00003

Isogai, Hirohisa. (2023). Training Effects of Multiple Target Tracking Skills. Journal of Biomechanical Society, 47(3), 166. https://doi.org/10.3951/sobim.47.3_166

Jensen, O., & Mazaheri, A. (2010). Shaping functional architecture by oscillatory alpha activity: gating by inhibition. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 4, 186. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2010.00186

Kane, M. J., Conway, A. R., Miura, T. K., & Colflesh, G. J. (2007). Working memory, attention control, and the N-back task: a question of construct validity. Journal of Experimental psychology: learning, memory, and cognition, 33(3), 615. http://www.apa.org/

Klimesch, W. (2012). Alpha-band oscillations, attention, and controlled access to stored information. Trends in cognitive sciences, 16(12), 606-617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2012.10.007

Komarudin, K., Mulyana, M., Berliana, B., & Purnamasari, I. (2021). NeuroTracker Three-Dimensional Multiple Object Tracking (3D-MOT): a tool to improve concentration and game performance among basketball athletes. Annals of Applied Sport Science, 9(1), 0-0.

Kucewicz, M. T., Cimbalnik, J., Matsumoto, J. Y., Brinkmann, B. H., Bower, M. R., Vasoli, V., … & Worrell, G. A. (2014). High frequency oscillations are associated with cognitive processing in human recognition memory. Brain, 137(8), 2231-2244. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awu149

Levitt, H. C. C. H. (1971). Transformed up‐down methods in psychoacoustics. The Journal of the Acoustical society of America, 49(2B), 467-477. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.1912375

Liu, C., Han, T., Xu, Z., Liu, J., Zhang, M., Du, J., … & Wang, Y. (2022). Modulating gamma oscillations promotes brain connectivity to improve cognitive impairment. Cerebral Cortex, 32(12), 2644-2656. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhab371

Owen, A. M., McMillan, K. M., Laird, A. R., & Bullmore, E. (2005). N‐back working memory paradigm: A meta‐analysis of normative functional neuroimaging studies. Human brain mapping, 25(1), 46-59. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20131

Parsons, B., Magill, T., Boucher, A., Zhang, M., Zogbo, K., Bérubé, S., … & Faubert, J. (2016). Enhancing cognitive function using perceptual-cognitive training. Clinical EEG and neuroscience, 47(1), 37-47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1550059414563746

Parsons, B., & Faubert, J. (2021). Enhancing learning in a perceptual-cognitive training paradigm using EEG-neurofeedback. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 4061. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-83456-x

Payne, L., & Sekuler, R. (2014). The importance of ignoring: Alpha oscillations protect selectivity. Current directions in psychological science, 23(3), 171-177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414529145

Riddle, J., McFerren, A., & Frohlich, F. (2021). Causal role of cross-frequency coupling in distinct components of cognitive control. Progress in Neurobiology, 202, 102033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2021.102033

Romeas, T., Guldner, A., & Faubert, J. (2016). 3D-Multiple Object Tracking training task improves passing decision-making accuracy in soccer players. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 22, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.06.002

Romeas, T., Goujat, M., Faubert, J., & Labbé, D. (2025). No transfer of 3D-Multiple Object Tracking training on game performance in soccer: A follow-up study. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 76, 102770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2024.102770

Roy, Y., & Faubert, J. (2022). Significant changes in EEG neural oscillations during different phases of three-dimensional multiple object tracking task (3D-MOT) imply different roles for attention and working memory. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.14470. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2207.14470

Tullo, D., Guy, J., Faubert, J., & Bertone, A. (2018). Training with a three‐dimensional multiple object‐tracking (3D‐MOT) paradigm improves attention in students with a neurodevelopmental condition: a randomized controlled trial. Developmental science, 21(6), e12670. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12670

Tétreault, É., Fortin-Guichard, D., McArthur, J., Vigneault, A., & Grondin, S. (2024). About the predictive value of a 3D multiple object tracking device for talent identification in elite ice hockey players. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 95(2), 370-383. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2023.2216266

Toscani, M., Marzi, T., Righi, S., Viggiano, M. P., & Baldassi, S. (2010). Alpha waves: a neural signature of visual suppression. Experimental brain research, 207(3), 213-219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-010-2444-7

Tuladhar, A. M., Huurne, N. T., Schoffelen, J. M., Maris, E., Oostenveld, R., & Jensen, O. (2007). Parieto‐occipital sources account for the increase in alpha activity with working memory load. Human brain mapping, 28(8), 785-792. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20306

Vater, C., Gray, R., & Holcombe, A. O. (2021). A critical systematic review of the Neurotracker perceptual-cognitive training tool. Psychonomic bulletin & review, 28(5), 1458-1483. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-021-01892-2

Vartanian, O., Coady, L., & Blackler, K. (2016). 3D multiple object tracking boosts working memory span: Implications for cognitive training in military populations. Military Psychology, 28(5), 353-360. https://doi.org/10.1037/mil0000125

Voss, M. W., Kramer, A. F., Basak, C., Prakash, R. S., & Roberts, B. (2010). Are expert athletes ‘expert’in the cognitive laboratory? A meta‐analytic review of cognition and sport expertise. Applied cognitive psychology, 24(6), 812-826. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1588

Webster, K., & Ro, T. (2020). Visual modulation of resting state α oscillations. eneuro, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1523/ENEURO.0268-19.2019

Zhang, H., Watrous, A. J., Patel, A., & Jacobs, J. (2018). Theta and alpha oscillations are traveling waves in the human neocortex. Neuron, 98(6), 1269-1281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2018.05.019

Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Q., Pan, X., Xu, G., & Li, J. (2025). Three-dimensional multiple object tracking (3D-MOT) performance in young soccer players: Age-related development and training effectiveness. PloS one, 20(8), e0312051. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0312051

Relevant Articles

-

Pilot study on changes in frontal oxygenated hemoglobin levels in beginners during practice of Karate Forms

by Kiyohisa Natsume - 2026,3

VIEW -

Why do you recall that smelly food? Effects of childhood residence region and potential reinforcing effect of marriage

by Yoshinori Miyamura - 2026,2

VIEW -

Accuracy of peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO₂) at rest determined by a smart ring: A Study in Controlled Hypoxic Environments

by Yohei Takai - 2025,6

VIEW -

A Study on the Effectiveness of Glycerophosphocholine (α-GPC) as an e-Sports Supplement

by Yuki Kamioka - 2025,5

VIEW