Search for Articles

Article Biology Life Sciences and Basic Medicine

Pilot study on changes in frontal oxygenated hemoglobin levels in beginners during practice of Karate Forms

Journal Of Digital Life.2026, 6,3;

Received:August 12, 2025 Revised:October 28, 2025 Accepted:January 30, 2026 Published:February 16, 2026

- Kiyohisa Natsume

- Kyushu Institute of Technology

- Junya Takaki

- Institute of Exercise Brain Science, Martial Arts Academy

Correspondence: natume@brain.kyutech.ac.jp

Abstract

Karate exhibits characteristics of several movement forms. This study investigated and compared cerebral oxygenated hemoglobin (∆oxyHb) levels, an indicator of brain activity, during form performances in Karate beginners. Significant increases in ∆oxyHb levels in the frontal region of the brain were observed during the performance of Karate Forms A, B, and C, as well as a radio exercise. Increases during Forms A and B were significantly greater than those during Form C and radio exercise. Rated perceived exertion (RPE) increased from Karate Forms A to C, with radio exercise exhibiting the lowest RPE. Although previous studies have suggested that cerebral ∆oxyHb tends to increase with rated perceived exertion, the relatively smaller ∆oxyHb change observed during Form C might be interpreted as reflecting greater cognitive effort and motor control demands in beginners. The modest ∆oxyHb response during the radio exercise might be related to higher motor familiarity and reduced cognitive requirements. Overall, these observations may imply that Karate practice is capable of engaging frontal brain regions in beginners, and that the degree of activation might be influenced by cognitive effort, motor control load, and familiarity with the movements.

1. Introduction

Karate is a martial art involving both defensive and offensive movements. Practitioners perform intense physical actions using their empty hands while engaging in complex intrinsic activities. Karate has two main components: form (Kata) and sparring (Kumite). Forms are movement patterns set against an imaginary opponent while Kumite is sparring with a partner to apply these techniques in real-time. Although Karate performance affects body physiology and metabolism (Chaabene et al., 2012; Rossi, 2021), research has also examined its effects on brain activity. A study obtained brain wave measurements during cognitive tasks and found that the Karate athlete group demonstrated higher alpha wave activity than the control non-athlete group (Duru & Assem, 2018). Furthermore, brain stimulation studies have shown shorter motor-evoked potential latencies in Karate groups than in control groups (Monda et al., 2017; Moscatelli et al., 2016). Karate performance affects brain activity involved in the motor function. Most studies have attempted to clarify the characteristics of karate athletes’ brain networks using cross-sectional studies to compare karate athletes and non-athletes. However, few longitudinal studies have been conducted. Thus, the effect of karate performance on the brain activity of non-athletes, including beginners, remains unclarified.

A wearable optical topography (WOT) system has been used to non-invasively monitor brain activity and measure changes in cerebral blood flow. These systems have been developed to be small, light, and wearable (Atsumori et al., 2009). The modified Beer–Lambert Law quantifies the WOT data for changes in oxygenated hemoglobin (oxyHb), deoxygenated hemoglobin (deoxyHb), and total hemoglobin levels. Of these, oxyHb levels, considered the most sensitive to task-related changes in brain activity, have been used as an index of brain neuronal activity (Hoshi et al., 2001). DeoxyHb levels do not necessarily reflect neuronal and metabolic activities in the brain; however, they are also affected by brain neuronal and metabolic activities. When neuronal activity increases, oxyHb levels usually increase and deoxyHb levels decrease (Meidenbauer et al., 2021) or do not change (Kenville et al., 2017).

Frontal oxyHb levels increase during attention-demanding walking tasks (Atsumori et al., 2009). A preliminary study revealed increased blood flow in the prefrontal region of veteran practitioners and beginners during Tai Chi Chuan performance (Kokubo et al., 2008). In Tai Chi Chuan, the co-activation of oxyHb levels in the frontal and sensory-motor areas occurs significantly less in the expert group than in the beginner group (Wang & Lu, 2022). Furthermore, this co-activation changes with Tai Chi exercise (Xie et al., 2019).

Changes in brain activation in beginners during the performance of Karate Forms remain unclear. Therefore, we conducted WOT measurements on beginners during their Karate Forms practice. To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate changes in the brain activity of beginners during Karate performance and examine how Karate practice affects brain activity.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

This study included 11 Japanese individuals (three females). Their mean age was 21.0 years (SD = 5.4, range 8–26). They had no Karate or other martial arts training experience. Thus, they were defined as beginners of Karate. Participants were recruited from an elementary school and a university. Their Leisure Score Index (LSI), assessed via the Japanese version of Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire (GLTEQ) (Godin & Shephard, 1985), was 29.9 (SD = 13.2, range 15–54). The Edinburgh Inventory (Oldfield, 1971) found that all participants were right-handed. None had any neurological abnormalities. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants. Two minors participated in the experiment. They were provided an explanation of the experiment in simple terms and presented with actual measuring instruments and illustrations. Consent was obtained from the minors and also their guardians. This study was approved by the Human Experimentation Committee of Kyushu Institute of Technology (approval number: 22-08).

2.2. Karate Form Performance

Karate has many Forms. In this experiment, we selected three basic Karate Forms that covered fundamental karate movements. These Forms involved only arm movements and minimized the influence of body motion on brain activity measurements. This allowed us to accurately evaluate how Karate-specific physical movements affected brain activity.

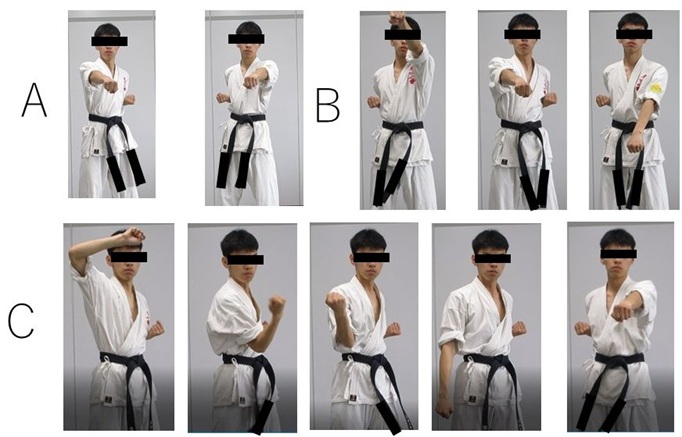

The three selected Forms were: 1) Seiken Chūdan tsuki (Forefist Middle-level straight punch) as shown in Fig. 1A: “Seiken” means forefist, “Chudan” refers to the mid-level target, and “tsuki” means punch. This punch focuses on delivering powerful strikes to vital areas, emphasizing correct hip rotation and proper stance stability. This fundamental punching technique involves a straight punch to the middle section with the right and left hands. Participants alternated left and right punches. The punch serves as the foundation for offensive techniques in Karate. 2) Seiken Jōdan-Chūdan-Gedan tsuki (Forefist upper-, middle-, and lower-level straight punches) as shown in Fig. 1B: This technique involves straight punches at three different heights: upper, middle, and lower levels. “Jōdan” refers to the upper body, Seiken Jōdan-tsuki refers to a straight punch aimed at the upper level, typically targeting the opponent’s face or head, and “Gedan” means lower level. Although less commonly used than Jōdan and Chūdan punches, a “Gedan” punch can be effective for close-range attacks and destabilizing the opponent. This technique requires full extension of the arm while keeping the wrist straight and striking with the first two knuckles. It combines offensive techniques to prepare practitioners for various situations. 3) Jōdan Age-Uke, Chūdan Soto-Uke, Chūdan Uchi-Uke, Gedan Barai, and Gyaku Tsuki (upper-level rising block, middle-level outer block, middle-level inner block, lower-level sweep, and reverse punches) as shown in Fig. 1C: “Age” means rising or lifting, “Uke” means block, “Soto” means outside, “Uchi” means inside, and “Barai” means sweep or parry. Thus, Jōdan Age-Uke is an upward block used to defend against an opponent’s attacks aimed at the upper level (head or face). Chūdan Soto-Uke is an outward block aimed at protecting the middle section, typically the torso. Chūdan Uchi-Uke is an inward block targeting middle-level attacks. Gedan Barai, also called Gedan Uke, is a downward sweeping block used to defend against low-level attacks, such as kicks to the groin or lower abdomen. Gyaku Tsuki is a reverse punch performed with the arm opposite the front leg in a stance. This form includes defensive techniques, such as upper-level rising blocks, middle-level outer and inner blocks, lower-level sweeps, and counterattacks using a reverse punch, all fundamental defensive and counterattack techniques unique to Karate. These three forms are referred to as Karate Forms A, B, and C. Participants were instructed not to move their heads or shoulders while performing these Karate Forms. These forms were selected because they provided an appropriate level of difficulty for beginners and reflected the essential elements of Karate’s offensive and defensive movements.

In addition to the above forms, participants also performed a radio exercise (Rajio Taisō) that they had previously experienced. Radio exercises comprise several types. Each participant performed one exercise. First, they opened their arms to the side and used momentum to return them to the starting position. They then swung their arms downward in front of the body and rotated them forward (Fig. 1 radio exercise). Radio exercises were limited to arm movements, similar to the three Karate Forms. Participants were asked not to move their heads; they were not asked for any other requests different from the Karate Form performances.

During Karate Forms and radio exercise practice, the Karate master (one of the authors, J. T.) stood in front of the participants, and they could see the master’s example. Participants performed the Karate Forms and a radio exercise simultaneously with the master in front of them. The master presented the sample.

The duration of each performance, including both the Karate Forms and radio exercise, was standardized to 30 sec. The participants repeated the performances for 30 sec. The order of the three Karate forms and radio exercise was pseudo-random for each participant to eliminate order effects and ensure a fair comparison. Furthermore, participants were allowed sufficient rest between performances to prevent fatigue or loss of concentration from affecting the results.

Rated perceived exertion (RPE) value was measured after each performance using the Borg scale (Borg, 1982). Two participants did not submit the scale questionnaire.

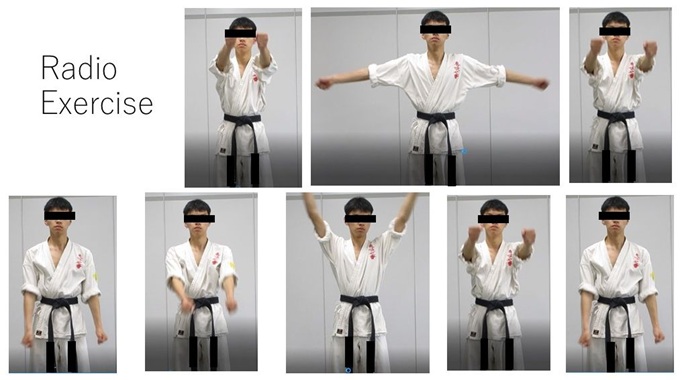

2.4. Measurements of oxyHb and deoxyHb levels at the frontal region of the brain

We measured the cerebral oxyHb and deoxyHb levels. OxyHb levels indicate brain activity during the performance of the three Karate Forms and radio exercise. DeoxyHb levels indicate changes in oxygen consumption and provide complementary information about neural activity during these performances. OxyHb and deoxyHb levels were measured in the frontal region of the brain using a wearable optical topography equipment (WOT-HS; NeU Co., Japan). The WOT-HS has 34 channels (including 3 × 11 channels and a reference channel), as shown in Fig. 2. Sampling frequency was set at 10 Hz. Among the 34 channels, the oxyHb and deoxyHb levels in 16 channels (channels 10–25) covering the frontal region of the brain (Fig. 2, top) were analyzed. Pre-processing involved: 1) manual deletion of the channels with oversaturated and signal-dropout light intensity during the performance, 2) use of the spline interpolation method (Scholkmann et al., 2014) to perform motion artifact correction, and 3) low-pass filtering of the oxyHb and deoxyHb levels with a cut-off frequency of 1 Hz to remove system and physiological noise. Onset of the performance was defined as 0 sec. Baseline was defined as the levels between -5 and 0 sec. Difference between baseline and performance oxyHb (∆oxyHb) and deoxyHb levels (∆deoxyHb) were calculated. These levels were normalized to the standard deviation of the baseline. We did not observe a significant difference in the change in ∆oxyHb level among 16 channels and three regions (mean value between channels 10–16, 17 and 18, 19–25 and in right, center, and left regions, respectively). Thus time–channel-averaged ∆oxyHb and ∆deoxyHb levels from the 16 channels during the performances were analyzed.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Significance probabilities were calculated via the open-source statistical software JASP (https://jasp-stats.org/). A significant difference was defined as a p < 0.05. Prior to conducting the analysis of variance (ANOVA), assumptions of normality and sphericity were assessed. When sphericity was violated, Greenhouse–Geisser correction (ε = 0.59) was applied to adjust the degrees of freedom.

3. Results

3.1. RPE for the karate forms performances and the radio exercise

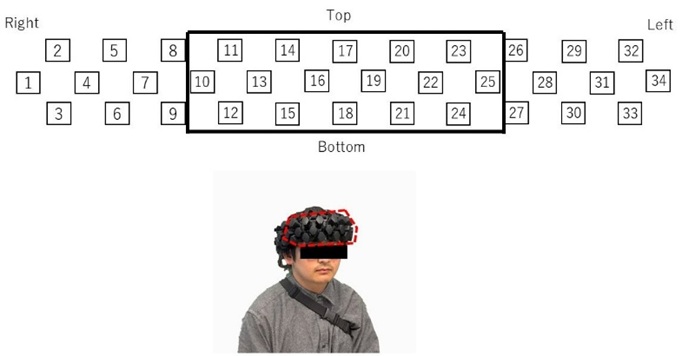

Mean RPE for the radio exercise and Karate Forms A, B, and C were 7.6 (SD = 1.6), 11.4 (SD = 2.8), 13.9 (SD = 1.7), and 16.2 (SD = 2.5), respectively, as shown in Fig. 3. RPE for radio exercise was the lowest among all the performances. RPE increased in Forms A to C. Form C exhibited the highest RPE. RPE values were significantly different among the three forms and radio exercise (as determined by one-way repeated measures ANOVA): F(1.8, 14.2) = 25.84, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.764). Post-hoc tests with Holm’s method revealed significant differences between the groups (t(8) = -3.12, Cohen’s d = -1.09, p = 0.036, Forms A vs. B; t(8) = -3.23, d = -2.14, p = 0.036, Forms A vs. C; t(8) = -3.23, d = -2.14, p = 0.034, Form A vs. radio exercise; t(8) = -3.13, d = -1.05, p = 0.036, Forms B vs. C; t(8) = -7.76, d = -2.84, p < 0.001, Form B vs. radio exercise; t(8) = -8.33, d = -3.89, p < 0.001, Form C vs. radio exercise).

3.2. Change in OxyHb levels (∆oxyHb) and DeoxyHb levels (∆deoxyHb) during Karate form performances

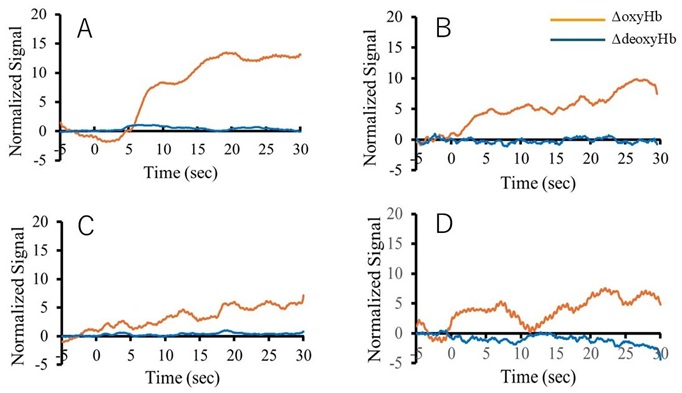

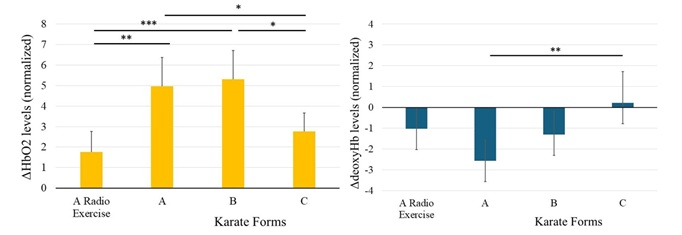

Fig. 4A to C illustrate the representative ∆oxyHb levels for a beginner performing Karate Forms A, B, and C. Increase during Form A was the largest, followed by that during Form B. Increase during Karate Form C was the lowest. ∆oxyHb levels also increased during the radio exercise (Fig. 4D), and was smaller than those in Karate Forms A and B. Fig. 5 left panel shows the statistical results. Mean ∆oxyHb levels during the radio exercise and Karate Forms A, B, and C performance were 1.8 (95% CI [0.9, 2.7]), 5.0 (CI [3.6, 6.4]), 5.3 (CI [4.0, 6.6]), and 2.8 (CI [1.8, 3.8]), respectively. All 95% CIs for oxyHb during the performance did not include zero. Thus, ∆oxyHb levels significantly increased (p < 0.05). Furthermore, ∆oxyHb levels during the performance of Forms A and B were significantly higher than those during Form C and radio exercise (as determined by one-way repeated measures ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test: F(3, 30) = 7.63, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.034; t(10) = 2.629, d = 0.28, p = 0.043, Forms A vs. C; t(10) = 3.6, d = 0.41, p = 0.002, Form A vs. radio exercise; t(10) = 3.0, d = 0.33, p = 0.013, Forms B vs. C; t(10) = 4.0, d = 0.45, p < 0.001, Form B vs. radio exercise). Conversely, ∆deoxyHb levels did not change substantially during all performances (Fig. 4). Fig. 5 right panel shows the statistical results. Mean ∆deoxyHb levels during the radio exercise and Karate Forms A, B, and C performance were -1.0 (CI [-2.1, 0.1]), -2.6 (CI [-3.6, -1.6]), -1.3 (CI [-2.3, -0.3]), and 0.2 (CI [-1.3, 1.7]), respectively. 95% CIs for ∆deoxyHb levels during performing Karate Forms A and B did not include zero, although those during Karate Form C and radio exercise included zeros. Thus, ∆deoxyHb levels did not change significantly during Karate Forms C and radio exercise. However, ∆deoxyHb levels significantly decreased during Karate Forms A and B (p < 0.05). ∆deoxyHb levels during the performance of Form A were significantly decreased compared with that during Form C (as determined by one-way repeated measures ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test: F(3, 30) = 3.78, p = 0.01, η2p = 0.02; t(10) = -3.35, d = -0.37, p = 0.0047, Forms A vs. C).

4. Discussion

Performances of the radio exercise and Karate Forms A, B, and C in beginners in this study had average RPE values of 7.6, 11.4, 13.9, and 16.2, respectively. Hence, the exertion required for the performance of radio exercise was extremely light. Furthermore, exertions for the performance of Karate Forms A, B, and C were light, somewhat hard, and hard (heavy), respectively. Compared with the radio exercise, which was performed unconsciously, Karate Forms require conscious effort to keep the head and shoulders still, thereby increasing intensity. Among Karate Forms, Form C was the most difficult to perform.

Mean RPE values reached approximately 16 during Karate Form C for 30 sec. While RPE 16 is typically classified as “hard” on Borg’s 6–20 scale, such ratings are generally observed during vigorous, sustained, whole-body exercise (Doherty et al., 2001). Doherty et al. (2001) recorded mean RPE = 16 after two minutes of treadmill running at 125% VO₂max with a 10.5% incline, a severe-intensity effort near exhaustion. The participants in the present study reported unexpectedly high RPE levels, as shown in Fig. 3. This discrepancy suggests that the RPE values may have reflected not only physical exertion but also mental effort, attentional demand (Lohse & Sherwood, 2011), or performance anxiety associated with reproducing the master’s movements sample under observation. Elevated RPE when performing Karate Form C may index cognitive-perceptual load in addition to physical exertion.

Karate beginners in this study had higher oxyHb levels in the frontal region of the brain when performing Karate Forms A and B than when performing Form C and the radio exercise (Fig. 4, and left panel in Fig. 5). Increase in levels while performing the radio exercise was as high as that while performing Karate Form C. Furthermore, increase in ∆oxyHb levels while performing Karate Forms A and B differed significantly from that during the radio exercise (Left panel in Fig. 5). ∆deoxyHb levels during the performances significantly decreased during performing Karate Forms A and B; however, they did not change during Karate Form C and radio exercise (Right panel in Fig. 5). When beginners performed Karate Forms A and B, ∆oxyHb levels increased, and ∆deoxyHb levels decreased. Those responses can reflect increases in neuronal and metabolic activity in the brain (Meidenbauer et al., 2021). Conversely, when ∆oxyHb levels increased, and ∆deoxyHb levels did not change as observed when performing Karate Form C and a radio exercise, neuronal and metabolic activities would increase and the increase may be small (Kenville et al., 2017). Brain activity includes both neuronal and metabolic activities. In addition, increase in ∆oxyHb levels during Karate Form C and a radio exercise was smaller than those during Karate Forms A and B. Hence, the obtained results suggest that activity in the frontal region of the brain will increase during performing Karate Forms A and B. However, it will not increase as much during performing Karate Form C and a radio exercise.

A previous study clarified that oxyHb levels in the frontal region of the brain increase depending on the RPE (Ishii et al., 2018). In this study, increase in ∆oxyHb levels during the performance of Form C was smaller than that during the performances of Forms A and B; although the RPE values monotonically increased in Forms A to C. Participants could easily mimic the master’s example with their “cognitive efforts” and “motor control capacities” when performing Forms A and B. Consequently, the performances were rated as light or somewhat hard according to their RPE values. As previously discussed, the performance of Form C would require physical exertion and also mental effort and attentional demand. In addition, their performance on Karate Form C may have induced anxiety to reproduce the master’s movement sample. Consequently, it would be difficult for the beginners to mimic the master’s example, and ∆oxyHb levels at the frontal region would decrease compared with those during the performance of Karate Forms A and B. During Form C, activation in other brain regions that process mental effort and attentional demand may lead to a decrease in the activation of the frontal brain region.

Increase in ∆oxyHb levels at the frontal region during radio exercise was significantly smaller than those during performing Karate forms A and B (left panel in Fig. 5). Furthermore, ∆deoxyHb levels did not change during the performance. Japanese individuals often perform a radio exercise starting from elementary school. Thus, the performance of a radio exercise was familiar for Karate beginners, while that of Karate Forms was novel. A previous study reported that oxyHb levels decreased as motor adaptation progressed (Polskaia et al., 2023). Thus, increase in ∆oxyHb levels during performing a radio exercise by Karate beginners may be lower than those during performing Karate Forms A and B due to the performance familiarity.

During performing three Karate Forms and radio exercise, all performances significantly increased ∆oxyHb levels in the frontal brain region of Karate beginners. Among the Karate Forms, Forms A and B significantly increased ∆oxyHb levels more than Form C and a radio exercise. RPE values increased monotonically from Karate Forms A to C. RPE values of the radio exercise were the lowest. Increase of ∆oxyHb levels in the frontal brain region of Karate beginners during performance might be modulated by “cognitive effort,” “motor control load,” and performance familiarity as well as physical exertion.

5. Future Works

These results were obtained from participants defined as Karate beginners (see Section 2.1). Their LSI values were relatively low compared to those of the average population (Bengoechea & Spence, 2002). Future studies should investigate whether Karate beginners who have higher LSI values exhibit similar results. ∆oxyHb levels at the frontal region should be measured when beginners develop sufficient body control without “cognitive effort,” “motor control load,” and anxiety after repetitive practice of Karate Form C. In addition, recruitment of Karate practitioners will enable us to stratify participants based on their Karate belt rank and years of experience. Subsequently, we can compare and examine the relationship between ∆oxyHb response at the prefrontal cortex and RPE, as well as activation changes in Form C, among beginners, intermediate practitioners, and advanced practitioners. Tai Chi, another martial art, affects cognitive abilities (Wayne et al., 2014). Thus, Karate performance may also affect them. Further studies are necessary.

6. Conclusions

We examined the effects of Karate. Forms and radio exercise performances on the change in ∆oxyHb at the frontal brain region. RPE values monotonically increased from Karate Forms A to C. Value for the radio exercise was significantly smaller than those for the Karate Forms. ∆OxyHb levels at the frontal brain region of Karate beginners increased during all the performances. Magnitudes of the increase during Karate Forms A and B were significantly larger than those during Form C and radio exercise. These results indicate that Karate Forms can increase frontal ∆oxyHb levels in the frontal brain. Karate Forms matched with the participants’ “cognitive efforts” and “motor control capacities” may result in a larger increase in ∆oxyHb levels. Karate Forms with high “cognitive effort” and “motor control load” may result in a smaller increase. Frontal ∆oxyHb levels in the brain of beginners might be modulated by “cognitive effort” and “motor control load” and performance familiarity as well as physical exertion. The hypothetical effects of Karate forms on ∆OxyHb levels at the frontal region of the brain should be clarified by the further study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K. N. and J. T.; Methodology, K. N.; Software, K. N.; Validation, K. N. and J. T.; Formal analysis, K. N.; Investigation, K. N. and J. T.; Resources, K. N. and J. T.; Data curation, K. N.; Writing—original draft preparation, K. N.; Writing—review and editing, K. N. and J. T.; Visualization, K. N. and J. T.; Supervision, K. N.; Project administration, K. N. and J. T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and its future amendments and approved by the Human Experimentation Committee of the Kyushu Institute of Technology (approval number: #22-08).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all of the participants involved.

Acknowledgments

KN would like to thank Prof. T. Shibata of the Kyushu Institute of Technology (KIT) for allowing us to use his WOT-HS and Smart Life Care Co-Creation LAB room at KIT. KN also thanks Y. Saito, A. Wakata, R. Nakamura, K. Jinnouchi, and Y. Iwamoto for their assistance with the experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Atsumori, H., et al. (2009). Development of wearable optical topography system for mapping the prefrontal cortex activation. Rev Sci Instrum, 80(4), 043704. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3115207

Bengoechea, G., & Spence, J. C. (2003). 2002 Alberta Survey on Physical Activity: A Concise Report.

Borg, G. A. (1982). Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 14(5), 377–381.

Chaabene, H., et al. (2012). Physical and physiological profile of elite karate athletes. Sports Med,42(10), 829–843. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03262297

Doherty, M., et al. (2001). Rating of perceived exertion during high-intensity treadmill running. Med Sci Sports Exerc,33(11), 1953–1958. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200111000-00023

Duru, A. D., & Assem, M. (2018). Investigating neural efficiency of elite karate athletes during a mental arithmetic task using EEG. Cogn Neurodyn,12(1), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11571-017-9464-y

Godin, G., & Shephard, R. J. (1985). A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can J Appl Sport Sci, 10(3), 141–146.

Hoshi, Y., et al. (2001). Interpretation of near-infrared spectroscopy signals: a study with a newly developed perfused rat brain model. J Appl Physiol,90(5), 1657–1662. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.2001.90.5.1657

Ishii, K., et al. (2018). Feedforward- and motor effort-dependent increase in prefrontal oxygenation during voluntary one-armed cranking. J Physiol,596(21), 5099–5118. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP276956

Kenville, R., et al. (2017). Hemodynamic response alterations in sensorimotor areas as a function of barbell load levels during squatting: an fNIRS study. Front Hum Neurosci,11, 241. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00241

Kokubo, H., et al. (2008). Research on brain blood flow during Taichi-quan by using fNIRS. J. Intl. Soc. Life Info. Sci., 26(1), 134–137.

Lohse, K. R., & Sherwood, D. E. (2011). Defining the focus of attention: effects of attention on perceived exertion and fatigue. Front Psychol,2, 332. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00332

Meidenbauer, K. L., et al. (2021). Load-dependent relationships between frontal fNIRS activity and performance: a data-driven PLS approach. Neuroimage,230, 117795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.117795

Monda, V., et al. (2017). Primary motor cortex excitability in karate athletes: a transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Front Physiol,8, 695. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.00695

Moscatelli, F., et al. (2016). Functional assessment of corticospinal system excitability in karate athletes. PLoS ONE,11(5), e0155998. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155998

Oldfield, R. C. (1971). The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia,9(1), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4

Polskaia, N., et al. (2023). Involvement of the prefrontal cortex in motor sequence learning: a functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) study. Brain Cogn,166, 105940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2022.105940

Rossi, L. (2021). Bioimpedance to assess the body composition of high-performance karate athletes: applications, advantages and perspectives. J Electr Bioimpedance,12(1), 69–72. https://doi.org/10.2478/joeb-2021-0009

Scholkmann, F., et al. (2014). A review on continuous wave functional near-infrared spectroscopy and imaging instrumentation and methodology. Neuroimage,85 Pt 1, 6–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.004

Wang, S., & Lu, S. (2022). Brain functional connectivity in the resting state and the exercise state in elite tai chi chuan athletes: an fNIRS study. Front Hum Neurosci,16, 913108. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2022.913108

Wayne, P. M., et al. (2014). Effect of tai chi on cognitive performance in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc,62(1), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12611

Xie, H., et al. (2019). Tai chi chuan exercise related change in brain function as assessed by functional near-infrared spectroscopy. Sci Rep, 9(1), 13198. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49401-9

Relevant Articles

-

Why do you recall that smelly food? Effects of childhood residence region and potential reinforcing effect of marriage

by Yoshinori Miyamura - 2026,2

VIEW -

Accuracy of peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO₂) at rest determined by a smart ring: A Study in Controlled Hypoxic Environments

by Yohei Takai - 2025,6

VIEW -

A Study on the Effectiveness of Glycerophosphocholine (α-GPC) as an e-Sports Supplement

by Yuki Kamioka - 2025,5

VIEW -

Wildlife Approach Detection Using a Custom-Built Multimodal IoT Camera System with Environmental Sound Analysis

by Katsunori Oyama - 2025,S2

VIEW