Search for Articles

A case study of the use of match video analysis tools in Judo: Attempts of visualizing the competition realities of an athlete

Journal Of Digital Life.2024, 4,S2;

Received:November 13, 2023 Revised:January 14, 2024 Accepted:February 6, 2024 Published:April 26, 2024

- Ryosuke Ozaki

- Faculty of Sports and Budo Coaching Studies, National Institute of Fitness and Sports in Kanoya

- Yuji Ozawa

- Faculty of Sports and Budo Coaching Studies, National Institute of Fitness and Sports in Kanoya

Correspondence: rozaki@nifs-k.ac.jp

Abstract

In this study, we analyzed match videos of a university Judo Player (Player A) utilizing the SPLYZA TEAMS matched video analysis tool. This is the first case study of Judo match analysis using the SPLYZA TEAMS software. A total of 13 matches involving Player A were analyzed in this study. Prior to the analysis, Player A formulated three hypotheses for the matching implementation. The analysis rejected two of the three hypotheses established at the beginning of the study. However, a notable trend emerged, revealing a proclivity for the Kumite situation for initiating Nage-waza from disadvantaged positions in matches that resulted in a loss. This novel finding was obtained by analyzing the data using the SPLYZA TEAMS software.

keywords:

1. Introduction

Judo is a Japanese martial art that was established in 1882 by Jigoro Kano. Judo practitioners wear Judo-gi, and engage in dynamic contests using Nage-waza and Katame-waza to assert dominance over their opponents. Since its recognition as an official sport at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics (Murata, 2011), judo has garnered international recognition, reaching over 200 countries and regions (International judo federation, 2023), making it a familiar facet of Japanese culture worldwide.

Despite the sport’s widespread practice, no studies or reports have analyzed competition videos using tools or applications related to competition analysis. While previous research has employed statistical methods to analyze Judo competitions and competitiveness (Ishii, et al., 2021; Maekawa et al., 2014) and analyzed score-earning tendencies based on competition videos, there remains a gap in comprehensive competition analysis, especially using approved tools (Miyake, et al., 2021; Ito et al., 2019). Moreover, the Scientific Research Department of the All Japan Judo Federation have developed its own competition video analysis tool, GOJIRA (Mynavi Books, 2017);however, this approach has yet to be approved for general use.

Although there are limited cases of competition analyses using competition videos for Judo, competition analysis is vital for enhancing competitiveness, analyzing opponents, and developing strategies.

Therefore, to address this, the present study attempts to analyze competitive Judo footage. As GOJIRA has not yet been approved for general use, we used SPLYZA TEAMS (https://products.splyza.com/teams/), a competition video analysis tool provided by SPLYZA Corporation. We analyzed competition video of Player A, a university student athlete for whom the author was involved in coaching. Player A sought to further improve his athletic performance at the time of this study in April 2022. Therefore, the author proposed the abovementioned visualization of the actual competition phase in SPLYZA TEAMS, and Player A agreed.

The characteristics of Player A are as follows: He was a 21-year-old male university student and judo competitor, with a Judo Dan of Second and 15 years of competition experience. Competing in the 81 kg weight class, he had placed 5th in the previous year’s national university championships at the time the analysis began (April 2022). He is a Right-Kumite in Judo’s competitive activities, and his favorite technique is Seoinage.

In this study, SPLYZA TEAMS was used to analyze Player A’s competition videos. This study focused a total of 13 of Player A’s games in 2021 and 2022. The competition results for 2021 and 2022 are as follows:

1) 2021 National Athletic College Tournament: lost in the 1st round (one match)

2) 2021 National University Championship: 5th place (four matches)

3) 2022 Japan National Championship: lost in the 2nd round (two matches)

4) 2022 Regional University Championship: champion (five matches)

5) 2022 Japan National Championship: lost in the 1st round (one match)

*National Championships were held twice in 2022, because the 2021 championship was postponed due to Covid-19. Thus, the competition for 2021 was held in 2022.

We used a competitive video analysis tool, SPLYZA TEAMS, which can be used on websites or through Smartphone and Tablet applications. SPLYZA TEAMS has be used for analyses of various sports, including basketball (Kiba, et al., 2022; Kitazawa, et al., 2019) and tennis (Kitamura, 2021). However, the analysis of Judo using this method has not been explored. Therefore, this is the first study to report a competitive analysis of Judo using SPLYZA TEAMS.

This study aimed to analyze Judo competition videos using analytical tools to visualize the reality of Judo competitions and seek cues for enhancing athletic performance.

To achieve this, we developed three hypotheses. While conducting this study, Player A believed that there was a difference in his attack style between matches that he won and lost. Based on this opinion, the author consulted with Player A and formulated the following hypotheses:

1) Player A heavily utilizes Seoinage and the Kouchi-gari associated with the preparatory movements of Seoinage.

2) Match outcomes correlate with the frequency of Player A’s Nage-waza.

3) In winning matches, Player A used Seoinage extensively, while lost matches involved fewer Seoinages.

2. Methods

2.1. Analysis using SPLYZA TEAMS

SPLYZA TEAMS facilitates the loading of competition videos and uses a function called “tags” to incorporate evaluation factors to the competition analysis (Fig. 1). While no predefined evaluation factors existed for Judo, the author (a 5th dan in judo and coach of a university judo team) and Player A collaboratively identified and developed the following evaluation factors (tags) specifically tailored for judo. In Judo, there are two skill systems, Nage-waza and Katame-waza, but because Player A primarily utilized Nage-waza as his main attacking technique, this analysis focused on Nage-waza.

2.1.1. General overview of the match

- Details of match settlements when victorious (Ippon, Yusei-gachi, Hansoku-gachi).

- Details of match settlements when defeated (Ippon, Yusei-make, Hansoku-make).

- Kumite stance combinations (Aiyotsu & Kenkayotsu).

*Aiyotsu: both competitors standing in a closed stance; Kenkayotsu: both competitors standing in an open stance (Ito, et al., 2015).

2.1.2. Match details

- Player responsible for initiating Nage-waza (Player A, Opponent player).

- Time periods attempting own Nage-waza in the match (0~1 min, 1~2 min, 2~3 min, etc.).

- Kumite situation when Nage-waza was performed (standard, advantaged situation, disadvantaged situation, one-sided grip, both collars or sleeves).

- Name of Nage-waza performed (Seonage, Uchi-mata, O-uchi-gari).

- Scores of Nage-waza (Ippon, Waza-ari, No.).

- Details of penalties (Shido) (non-combativity, not taking a grip, defensive position, Illegal Kumi-kata, etc.)

- Object of penalties (Shido) (Player A, Opponent, both players).

2.2. Conducting Analysis

Player A, in collaboration with the author, conducted the analysis after the last match (the 2022 Japan National Championship). To validate the study’s hypotheses, the videos of all matches were tagged, and the tags were systematically tabulated for each match won and lost. Additionally, we examined Player A attack strategy in each match. The tag summary data were obtained from SPLYZA TEAMS in Microsoft Excel. A graph was then created based on the tag summary data.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of the matches

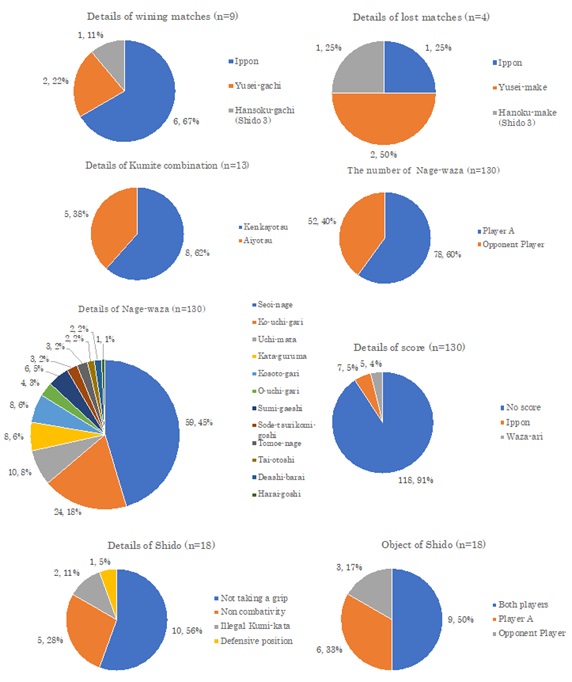

A summary of the 13 matches is presented in Fig. 2. Of the nine winning matches, Ippon won six (67%), Yusei-gachi won two (22%), and Hansoku-gachi by Shido3 won one (11%). Of the four lost matches, Ippon had one (25%), Yusei-make had two (50%), and Hansoku-make by Shido 3 had one (25%). The Kumite combinations of Player A and Opponent were five (38%) for Aiyotsu and eight (62%) for Kenkayotsu. Nage-waza occurred 130 times in the 13 games, with 78 instances by Player A (60 %) and 52 by the Opponent (40 %).

The Nage-waza comprised 12 types, including 59 (45%) Seoinage, 24 (18%) Kouchi-gari, and 10 (8%) Uchi-mata, in descending order of frequency. For the Nage-waza evaluation, there were 118 (91%) instances of no score, seven (5%) of Waza-ari, and five (4%) of Ippon. There were 18 instances of shido in the 13 games, with “Not taking a grip” accounting for 10 (56%), “Non-combativity” for five (28%), “Illegal kumi-kata” for two (11%), and “Defensive position” for one (5%). The “Illegal kumi-kata” occurred in two (11%), and “Defensive position” occurred in one (5%) match. The object of Shido was nine (50%) for both players, six (33%) for Player A three (17%) for the Opponent players.

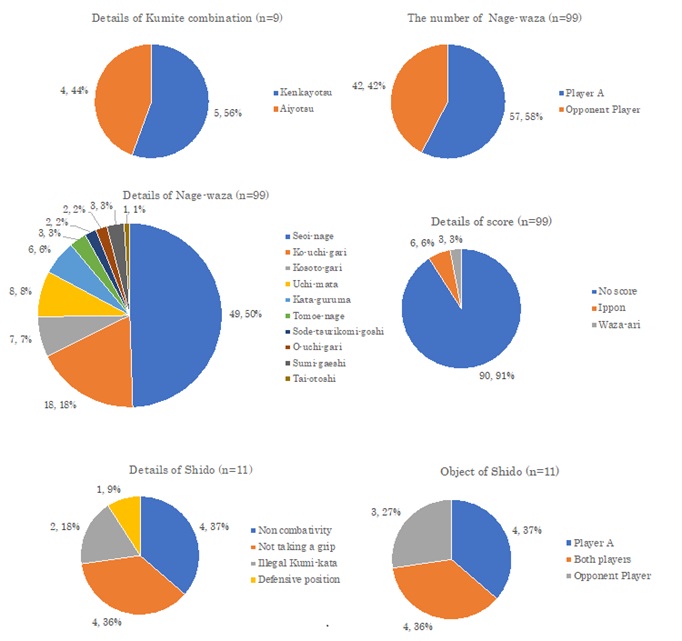

3.2. Details of the winning matches (Player A and Opponent players’ summary)

The details of the nine winning matches are summarized in Fig. 3. The Kumite combinations of Player A and Opponent players were four (44%) for Aiyotsu and five (56%) for Kenkayotsu. Ninety-nine Nage-waza were performed in the nine games, with 57 (58%) by Player A and 42 (42%) by Opponents. Nage-waza comprised 10 different types, with Seoinage accounting for 49 (50%), kouchi-gari for 18 (18%), and kosoto-gari for seven (7%). Nage-wazas were evaluated with a no score of 90 (91%); Ippon at six (6%); and Waza-ari at three (3%). Shido instances totaled 11 in nine games, with four (37%) for “Non-combativity,” four (36%) for “Not taking a grip,” two (18%) for “Illegal kumi-kata,” and one (9%) for “Defensive position.” Illegal kumi-kata” accounted for two (18%) and “Defensive position” for one (9%). The Object of Shido was Player A with four (37%), both players with four (36%), and Opponent players with three (27%).

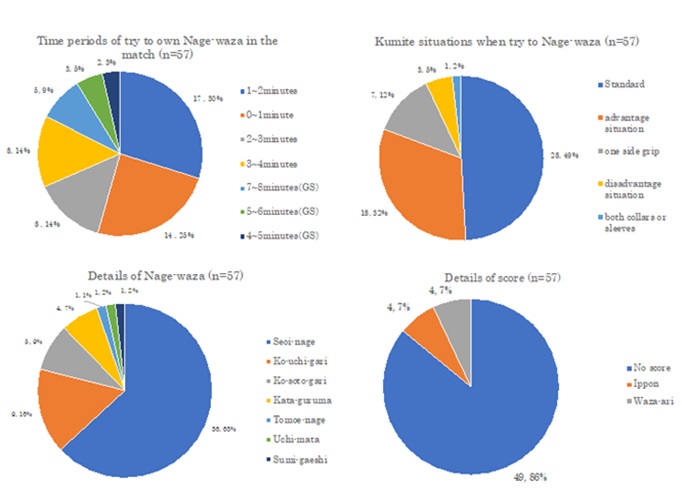

3.3. Player A’s content in the winning matches

To verify the Nage-waza setups by Player A in the winning matches, tags were tabulated, focusing on Player A’s Nage-waza, and a graph was created. A detailed description of Player A’s nage-waza (n=57) in the winning match is shown in Fig. 4. The most common time period that Player A performed Nage-waza was “1~2 min”, accounting for 17 (30%) of the total instances, followed by “0~1 min” and “2~3 min”. The “Standard” Kumite situation when Nage-waza was performed was the most common, accounting for 28 (49%) of the total. The advantageous situation accounted for 18 (32%). Seoinage accounted for 36 (63%), followed by Kouchi-gari with nine (16%). Nage-waza evaluations resulted in no score for 49 (86%), Ippon for four (7%), and Waza-ari for four (7%).

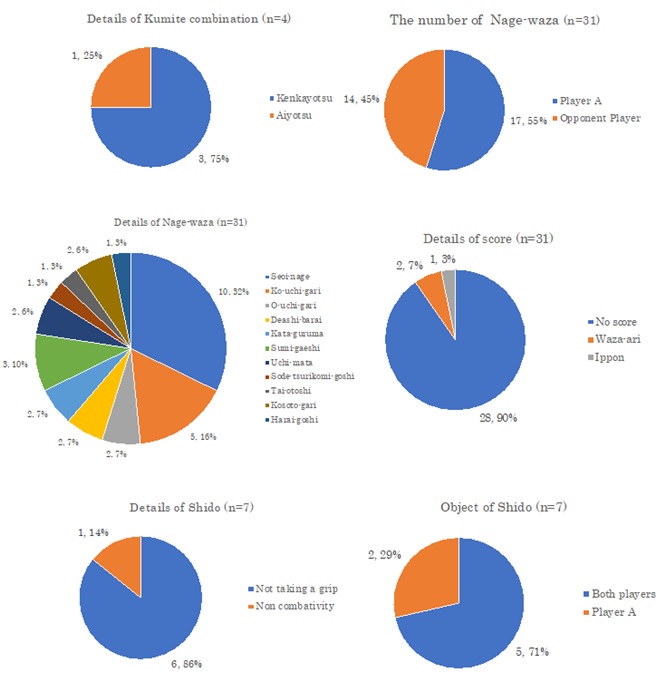

3.4. Details of the lost matches (Player A and Opponent players’ summary)

The four games lost matches are illustrated in Fig. 5. The Kumite combination of Player A and Opponent players was one (25%) for Aiyotsu and three (75%) for Kenkayotsu. The number of Nage-wazas conducted in the four matches was 31, with 17 (55%) by Player A and 14 (45%) by Opponent players. Nage-waza comprised 11 different types, with Seoinage accounting for 10 (32%), Kouchi-gari for five (16%), and Ouchi-gari for two (7%). Nage-waza was evaluated with no score at 28 (90%), Ippon at one (3%), and Waza-ari at two (7%). Shido instances totaled seven in four matches, with six (86%) for “Not taking a grip” and one (14%) for “Non-combativity.” There were five (71 %) objects of shido for both players and two (29%) for Player A.

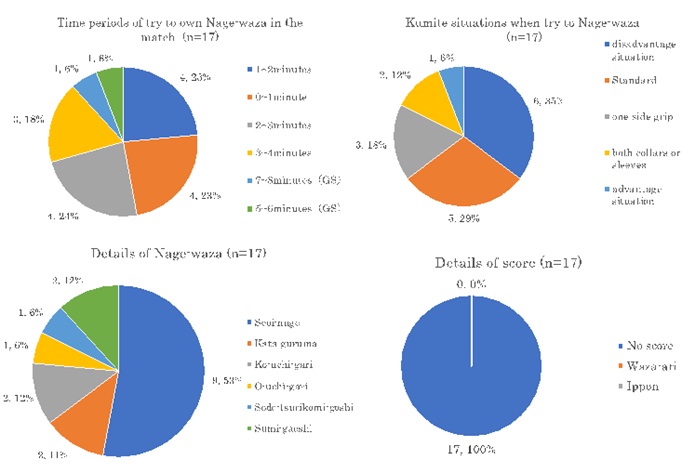

3.5. Player A’s content in the lost matches

To verify the Nage-waza Player A setups in the lost matches, tags were tabulated, focusing on Player A’s Nage-waza, and a graph was created. The details of Player A’s Nage-waza (n=17) in the lost matches is shown in Fig. 6. The most common time period for Player A to perform Nage-waza was “1~2 min”, accounting for four (23%) of the total, followed by “0~1 min” and “2~3 min”. Kumite situations when Nage-waza was performed were as follows: “Disadvantage situation” in six (35%), “Standard” in five (29%), “One side grip” in three (18%), “Both collars or sleeves” in two (12%), and “Advantage Situation” in one (6%). Nine (53%) were Seoinage and two (11%) were Kata-Guruma. None of the Nage-waza evaluations were scored.

4. Discussion

4.1. About overview of the matches

Focusing on the winning matches in Fig. 2, six out of nine matches were Ippons, indicating Player A’s proficiency with the most Ippons. Regarding the number of Nage-wazas, Player A had 60% and Opponent players had 40%. Regardless of the match outcome, Player consistently took the lead in initiating a larger percentage of Nage-wazas. Regarding the evaluation of Nage-waza, no scores accounted for 91%, indicating the difficulty in obtaining a score for Judo. Regarding Shido instances, “Not taking a grip” was the most common response, and both players accounted for 50% of the objects in Shido. This implies an intense struggle by both players to manipulate the Kumite situation in their favor, underscoring the competitive intensity observed in the analyzed matches.

4.2. Details of the winning matches

Focusing on Fig. 3, Aiyotsu and Kenkayotsu account for almost half of the total number of Kumite combinations. Indicating Player A’s weakness in either Aiyotsu or Kenkayotsu. Regarding the number of Nage-wazas, Player A accounted for 58% and Opponent players for 42%; therefore, Player A was not considered the more dominant player. However, regarding the type of Nage-waza, Seoinage accounted for 50% and Kouchi-gari for 8%. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is likely to be supported, although a detailed examination of the percentage of Player A’s Nage-waza is warranted.

4.3. Player A’s content in the winning matches

Examining Player A’s performance in the winning matches, in Fig. 4, reveals that half of the Nage-waza instances occurred within the “1~2 min” and “0~1 min” time periods, suggesting a propensity for initiating Nage-waza early in the match. However, the number of Nage-wazas did not significantly decrease in later time periods, suggesting that Player A is an endurance player. In Kumite situations when Nage-waza was executed, “Standard” was the most popular (49%), followed by the “Advantage situation” (32%). This indicates that Player A primarily executed Nage-waza in the “Standard” or “Advantage situation” during the winning matches. Analyzing Player A’s specific Nage-waza in winning matches, Seoinage and Kouchi-gari accounted for 63% and 16%, respectively, of the total of 79%. This aligns with Hypothesis 1 that “Player A uses a lot of Seoinage and the Kouchi-gari associated with the preparatory movements of Seoinage.”

4.4. About details of the lost matches

The lost matches are shown in Fig. 5. The analysis of the number of Nage-wazas in the lost matches revealed that Player A initiated 55%, while the Opponent player initiated 45%. Interestingly, this percentage distribution mirrors the results observed in the winning matches (58% for Player A and 42% for Opponent Players). Thus, Player A’s percentage of initiating Nage-waza was consistent regardless of whether he won or lost. Consequently, Hypothesis 2, ” Winning or losing a match is related to the number of one’s own Nage-waza,” was rejected.

4.5. Player A’s content of the lost matches

The analysis of Player A’s in lost matches are shown in Fig. 6. The time periods of Nage-waza were “1~2 min” and “0~1 min” in 46% of cases, consistent with that of the winning matches. Regarding the nage-waza content, seoinage was the most common (53%), followed by kouchi-gari (12%), similar to in the winning matches. This contradicts Hypothesis 3, ” Winning matches use a lot of Seonage. In other words, lost matches did not use many Seonages.” Furthermore, the analysis of Kumite situations when initiating Nage-waza in lost matches reveals that the “Disadvantage situation” was the most common (35%), followed by “Standard” (29%), “One side grip” (18%), “Both collars or sleeves” (12%), and “Advantage situation” (6%). The “Disadvantage situation” was uncommon in the winning matches (5%), and the “Advantage situation” was the most common (49%), indicating that the Kumite situation in the losing matches differed from that in the winning matches. In the lost matches, the number of Nage-waza in the “disadvantage situation” was high, suggesting that Player A struggled to gain an advantage in Kumite-scramble during the lost matches; this contradicts the initial hypothesis. This underscores the importance of video analysis in uncovering nuanced aspects of performance, as demonstrated by SPLYZA TEAMS in this study.

5. Conclusions

The author and Player A formulated three hypotheses to understand match reality. Utilizing SPLYZA TEAMS for video analysis led to the rejection of two hypotheses. Notably, the comparison between winning and lost matches revealed that in lost matches, the Kumite situation often started with “Disadvantage situation” followed by the initiation of Nage-waza. This discrepancy between athletes between athletes’ perceptions and the analytical insights provided by SPLYZA TEAMS highlights the value of such tools in objectively evaluating match dynamics. While the initial hypotheses were disproven, a significant revelation emerged: Nage-waza in lost matches tended to originate from a disadvantaged Kumite situation. For Player A, enhancing Kumite skills became a pivotal factor in elevating competitive performance. This study not only refuted preconceived notions but also offered valuable insights for targeted improvement in Player A’s approach to matches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R. O.; methodology, T. O. and D. F.; software, R. O.; validation, R. O. and Y. O.; formal analysis, R. O.; writing—original draft preparation, R. O.; writing—review and editing, R. O. and Y. O.

Funding

This study was supported by the Priority Project of the National Institute of Fitness and Sports in Kanoya, titled ICT Support Project for Improvement of Match Performance: Video Sharing and Game Performance Analysis Using Cloud Computing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

International judo federation (2023). Retrieved November 2,2023, from https://www.ijf.org/countries

Ishii, T., Suzuki, Y. (2021). Development of a method for evaluating athletic performance in competitive matches using rating, https://takanoriishii.jp/rating_wjc2021/#title1 (Last access date: 2023/11/02).

Ito, K., Hirose, N., Maekawa, N. (2019). Characteristics of Re-gripping Techniques Preceding Scored Throws in International-level Judo Competition. Central European Journal of Sport Sciences and Medicine, 25(1), 43-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.18276/cej.2019.1-05

Ito, K., Hirose, N., Maekawa, N., Tamura, M., Nakamura, M. (2015). Alterations in Kumite Techniques and the Effects on Score Rates Following the 2013 International Judo Federation Rule Revision. Archives of Budo, 11, 87–92.

Kiba, K., Wada, T., Takahashi H. (2022). Effect of introducing the video analysis application to women’s basketball team of K-University: Focused on the understanding of the individual technique and the team tactics. Academic journal bulletin of National institute of fitness and sports in Kanoya, 59, 37-46. https://nifs-k.repo.nii.ac.jp/records/1203

Kitamura, T. (2021) Support programs for Japan Tennis Association’s high-performance in the 2020 Tokyo Olympic games. Bulletin of Biwako Seikei Sport College, 19,153-171. http://hdl.handle.net/10693/00005756

Kitazawa, T., Takahiro, F., Doi, H., Hirasawa, M., Komura, S. (2019). Effects of Reflection of Basketball Game Videos using a CSCL System Focus on Junior High School Students’ Activity Recording, Ability to think and Awareness of Club Activities. Journal of Japan Educational Research Society of the AI era, 1,7-12. https://doi.org/10.50948/esae.1.0_7

Maekawa, N., Ito, K., Ishii, K., Koshino, T., Yazaki, R., Tamura, M., Hirose, N. (2014). A study of validation of competitive abilities scale of judo competitors by using AHP. Research Journal of Budo, 47 (1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.11214/budo.47.1

Miyake, K., Takezawa, T., Ito, K., Sato, S., Hirose, N. (2021). Tactical actions of nage-waza effective for scoring in judo. Research Journal of Budo, 54 (2), 103-113. https://doi.org/10.11214/budo.2110

Murata, N. (2011) Internationalization of Judo, Nippon Budokan.

Mynavi Books (2017). “GOJIRA” Analysis Software Supports Japanese Judo: Balance between “Quantitative” and “Qualitative” is Important, https://book.mynavi.jp/macfan/detail_summary/id=86615(Last access date: 2023/11/02).

Relevant Articles

-

A Study on the Effectiveness of Glycerophosphocholine (α-GPC) as an e-Sports Supplement

by Yuki Kamioka - 2025,5

VIEW -

Wildlife Approach Detection Using a Custom-Built Multimodal IoT Camera System with Environmental Sound Analysis

by Katsunori Oyama - 2025,S2

VIEW -

Clarifying the Sharpened network diversity in French flair rugby

by Koh Sasaki - 2024,2

VIEW -

A proposal concerning exercise intensity with the Nintendo Ring Fit Adventure Exergame among older adults: A preliminary study

by Ryo Miyazaki - 2023,12

VIEW