Search for Articles

Article Education Psychology and Education

Exploring Undergraduate Students’ Transformative Learning Experiences through an eHealth Literacy Workshop in Japan

Journal Of Digital Life.2026, 6,1;

Received:October 7, 2025 Revised:November 24, 2025 Accepted:December 9, 2025 Published:January 7, 2026

- Takafumi Tomura

- Department of Economics, Fukuyama University

- Yohei Yamashita

- Department of Economics, Fukuyama University

- Mijung Choi

- Department of Economics, Fukuyama University

Correspondence: t.tomura@fukuyama-u.ac.jp

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to explore Japanese undergraduate students’ transformative learning experiences during an eHealth literacy workshop. Grounded in transformative learning theory, the study employed a descriptive qualitative approach using an explanatory case study design. Six undergraduate students who participated in the workshop completed a demographic questionnaire and a semi-structured interview. Data were analyzed using the constant comparative method, resulting in three major themes: (Theme I) learning about searching strategies to identify problematic assumptions, (Theme II) task-oriented learning to develop evaluation skills, and (Theme III) necessity of learning eHealth literacy for students who live alone. The findings emphasize the importance of prioritizing eHealth literacy in Japanese universities to prevent students from engaging in risky health information practices. Therefore, we hope the findings will contribute to the development of both formal and informal eHealth literacy education in Japanese universities, enhancing students’ capacity to become effective and responsible seekers of online health information.

1. Introduction

Undergraduate students represent a vital segment of the population, with the potential to become future leaders, policymakers, and professionals. Accordingly, promoting their physical, mental, and social well-being has become a global public health priority. However, university life coincides with a transitional period marked by academic pressure, financial strain, adaptation to independent living, and uncertainty about careers (Adeoya, 2025). These challenges place students at risk for chronic diseases, poor dietary habits, risky sexual behaviors, and mental health problems such as stress, anxiety, and depression (e.g., Hamilton et al., 2021). Many of these issues are linked to low health literacy, defined as the ability to access, interpret, and understand essential health information to make informed decisions (Berkman et al., 2011). In Japan, undergraduate students’ health literacy is comparatively lower than that of peers abroad (Adeoya, 2025), raising concerns for Generation Z and Alpha, who are constantly exposed to vast amounts of online health information (Papp-Zipernovszky, 2021). In this context, there is an urgent need to provide education that equips students with the skills to search for, evaluate, and apply digital health information effectively.

Electronic resources now play a central role in students’ health behaviors, with the Internet serving as the primary source for health information (Stellefson et al., 2011). Social networking services (SNS) such as X, Instagram, YouTube, TikTok, and Facebook dominate daily life. In Japan, students use smartphones extensively, relying on SNS not only for communication but also for social connection (Takahashi, 2014). However, students often overestimate the credibility of online health information, placing greater trust in social media, blogs, or celebrity websites than in evidence-based sources (Chen et al., 2024). This overreliance is problematic, as social media platforms frequently disseminate misleading content, posing risks to students’ decision-making and well-being (Moorhead et al., 2013). To address this, students need transformative learning experiences that encourage them to question assumptions, critically assess credibility, and make informed health decisions.

The originality of this study lies in offering beneficial and practical insights for designing effective eHealth literacy education for undergraduate students in Japan. eHealth literacy refers to the ability to search for, understand, evaluate, and use online health information, supported by six interrelated literacies: traditional, health, information, scientific, media, and computer (Norman, 2006). To better understand how Japanese undergraduates develop these skills, this study examined their transformative learning experiences during an eHealth literacy workshop designed by the researchers. Guided by this aim, the study addressed the following research questions:

- What did Japanese undergraduate students learn during the workshop regarding eHealth literacy?

- How did their participation in the workshop prompt them to identify and transform misconceptions about using online health information?

Developing eHealth literacy is especially important for undergraduate students, who routinely rely on digital media for health information but may lack the knowledge and skills to critically evaluate it. The American College Health Association (2024) highlights seven key health domains: (a) alcohol, tobacco, and drug use; (b) sexual health; (c) weight, nutrition, and exercise; (d) mental health; (e) personal safety and violence; (f) food insecurity and homelessness; and (g) sleep, which are also relevant to Japan. For example, social media contributes to body-image misconceptions among Japanese female students, heightening risks of underweight and malnutrition (Nagashima et al., 2024). Despite these concerns, research on how Japanese undergraduates develop eHealth literacy remains limited, underscoring the need for evidence-based educational approaches.

To address this gap, the researchers developed and implemented an eHealth literacy workshop tailored to Japanese undergraduates. The workshop combined theory-based instruction with practical learning activities to help students acquire skills for searching, evaluating, and applying online health information while critically examining their assumptions. A central component was group discussion (Sato et al., 2017), which cultivated critical thinking by encouraging students to reflect on assumptions and engage in dialogue around accuracy and credibility. Through this process, students were expected to revise their beliefs and integrate evidence-based practices into their daily lives when navigating online health information.

1.1 Theoretical framework

This study was grounded in transformative learning theory (Mezirow, 2018), a component of adult learning theory. It explains how adults form frames of reference based on assumptions, beliefs, and expectations, which they use to interpret experiences. In undergraduate education, transformative learning is understood as a process in which individuals engage in critical self-reflection to revise problematic frames of reference, leading to more inclusive and integrative understandings (Mezirow, 2018). Guided by this perspective, the researchers used this framework to examine how undergraduates transform beliefs about online health information through the eHealth literacy workshop.

Transformative learning involves two domains: instrumental and communicative (Mezirow, 2018). The instrumental domain focuses on solving problems through reasoning and interaction with the environment. For example, students learn cause-and-effect relationships by formulating hypotheses, testing, and analyzing results (Brownell et al., 2015). In eHealth literacy, this appears in students’ use of evidence-based measures to evaluate information and distinguish accuracy. The communicative domain concerns understanding one’s purposes, values, and beliefs, as well as those of others, through communication (Mezirow, 1997). Here, critical reflection helps students identify assumptions through acts such as hearing diverse views, collaborative problem-solving, and self-reflection. This domain contributes to students’ personal and social identity, enabling more reflective, critical approaches to problem-solving.

In eHealth literacy, students must critically reflect to examine, question, and revise assumptions about using online information to improve health (Mezirow, 1991, 1997). Workshops should facilitate this reflection, enabling students to experience four learning processes (Mezirow, 1997). First, elaborating on existing views by seeking evidence that supports initial assumptions. Second, establishing new perspectives when encountering unfamiliar ideas, often first interpreted negatively, prompts questioning of credibility and relevance. Third, transforming viewpoints through reflection on misconceptions, fostering openness to alternative perspectives. Fourth, transforming habits of mind, particularly ethnocentric or generalized assumptions. Through self-awareness and deep reflection, students can identify their implicit biases and adopt more inclusive and evidence-based approaches to evaluating online resources.

2. Methods

A descriptive-qualitative methodology using an explanatory case study design (Yin, 2003) was adopted in this study. The case study method is typically used by researchers to understand complex educational and/or social phenomena while maintaining the meaningful uniqueness of real-life circumstances (Yin, 2003). More specifically, an explanatory case study design enables researchers to explore in depth the how, why, and what aspects embedded in the research questions (Schwandt, 2015). Accordingly, this design was selected to capture beneficial insights into what Japanese undergraduate students learn during the eHealth literacy workshop and how this learning transforms their perceptions and potential future behaviors. This approach allowed the researchers to examine how students may begin to apply eHealth literacy concepts in their daily lives, particularly in their search for, evaluation of, and use of appropriate and trustworthy health information. Using transformative learning theory as the theoretical framework, the researchers sought to interpret students’ critical reflection experiences and the ways in which the workshop reshaped their perceptions, feelings, and cognition (Closs et al., 2011). To capture these transformative processes, semi-structured interviews were conducted after the workshop as the primary data collection method. In addition, a demographic questionnaire was administered to assess students’ baseline eHealth literacy, enabling the researchers to examine how their understanding and perceptions changed over time through participation in the workshop.

2.1 Participants and Setting

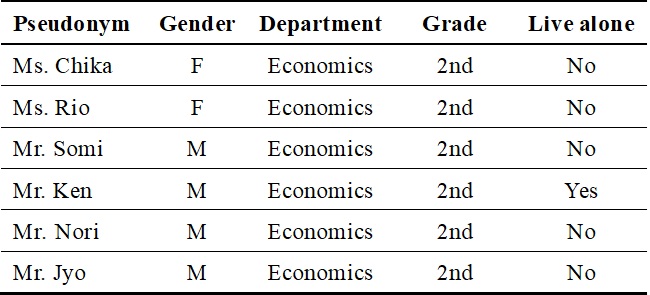

Six undergraduate students (male n = 4; female n = 2) were recruited by purposeful sampling (Patton, 2014) from one university located in Chugoku region in Japan. All participants attended the eHealth literacy workshop, which the researchers collaboratively organized, and held as a compulsory second-year course known as the Basic Seminar, which all sophomores are required to complete. Although each instructor typically delivers predetermined instructional content within their respective seminar groups, this particular class session allowed instructors to design their own activities. Taking advantage of this flexibility, the three researchers collaboratively planned and delivered the eHealth literacy workshop. A total of 30 undergraduate students enrolled in the seminar groups supervised by the three researchers participated in the workshop. Prior to implementing the workshop, the researchers established sampling criteria that required students to (a) respond to the questionnaire survey before the workshop, (b) have prior experience searching for health information online, and (c) admit that they faced difficulties in using online health information. Criteria (b) and (c) were established based on transformative learning theory, which suggests that meaningful learning occurs when students recognize limitations in their current ways of thinking and engage in critical reflection to develop new perspectives (Tomura et al., 2024). Among the 30 students, 21 met criteria (a) and (b). However, only six of these students provided consent to participate in the semi-structured interviews. After confirming that these six students also met criterion (c), they were selected as the research participants for the current study. All participants (Ms. Chika, Ms. Rio, Mr. Somi, Mr. Ken, Mr. Nori, Mr. Jyo) met these sampling criteria and were assigned pseudonyms to protect their privacy and ensure anonymity.

Table 1. Participants’ demographic information

2.2 Data collection

2.2.1 eHealth literacy workshop

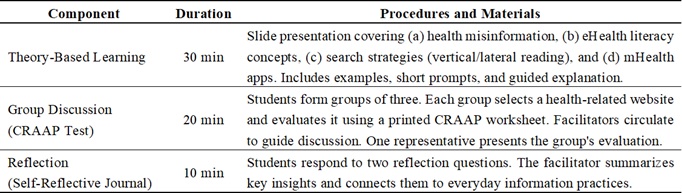

The eHealth literacy workshop was conducted in a single session, facilitated by three researchers involved in this study. Its primary aim was to provide Japanese undergraduate students with foundational knowledge and practical learning experiences to foster eHealth literacy, thereby enabling them to search for, analyze, and apply online health information in their daily lives. The overview of the eHealth literacy workshop procedure is listed in Table 2. To enhance replicability and transparency, detailed procedures and instructional materials for each component are described below.

In a theory-based learning session, a lecture-style segment supported by a slide presentation, the researchers introduced key concepts to help undergraduate students understand what eHealth literacy is, why its development is necessary, and how it can be applied in daily life. The session addressed four topics: (a) the social impact of health misinformation, (b) the definition and significance of eHealth literacy, (c) evidence-based search strategies such as vertical and lateral reading, and (d) examples of mHealth applications commonly used in daily life. Each topic included an illustrative example (e.g., past news stories claiming that health-related issues were caused by misinformation that was prevalent on the Internet). To ensure that the learning content was appropriate for students’ level of understanding, the researchers engaged in multiple rounds of discussion before finalizing these topics.

The group discussion session adopted a task-oriented learning approach by applying the Currency, Relevance, Accuracy, Authority, and Purpose (CRAAP) test (Meriam Library of CSU Chico, 2010). This approach provided students with hands-on opportunities to use an evidence-based framework, thereby stimulating critical thinking, challenging assumptions, and enhancing eHealth literacy. Specifically, students were divided into 10 groups of three and provided a CRAAP worksheet and instructions to identify a health-related website and assess its reliability using the CRAAP test. Throughout the activity, the researchers circulated among the groups to pose guiding questions and encourage deeper analysis. Following the discussions, representatives from each group presented their evaluations to the class, enabling cross-group comparisons and collective reflection on the credibility of the selected websites.

In the reflection session, the final segment of the workshop, the study used a self-reflective journal (Hodge et al., 2003; Tomura et al., 2024) to encourage students to reflect on their learning experiences, including their personal opinions, feelings, and beliefs. All participants were asked to respond to two reflective questions using Microsoft Forms, which are: (a) What did you learn from the eHealth literacy workshop, and how would you like to apply it in your daily life? (b) Why do you believe it is essential for undergraduate students to learn about eHealth literacy? After all students completed their reflections in a self-reflective journal, the researchers concluded the session by summarizing key insights from the group presentations and leaving take-home messages to encourage them to apply their new learning in their real lives to develop and promote healthy lifestyles.

Table 2. Overview of the eHealth literacy workshop procedures

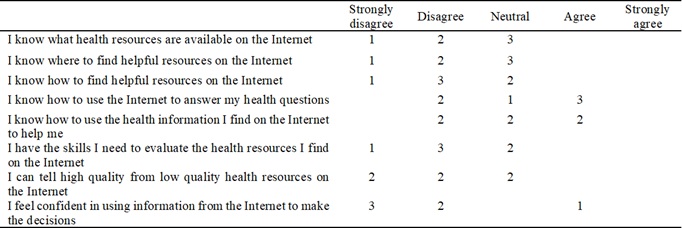

2.2.2 Demographic questionnaire

The study used a demographic questionnaire created using a sample of items from the Japanese version of eHealth literacy scale, which was translated by Mitsutake et al. (2011) based on the original version created by Norman et al. (2006). This scale was developed based on six key literacies, which include two areas of analytic literacy (traditional literacy and numeracy, media literacy, information literacy) and context-specific literacy (computer literacy, science literacy, health literacy). The questionnaire included eight items and used a Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree; 2 = Disagree; 3 = Undecided; 4 = Agree; 5 = Strongly Agree). The demographic questionnaire was completed by all participants before participating in the interviews. The researchers used the demographic questionnaire to collect descriptive background information specifically about the six focal participants, rather than to generate quantitative findings. This information was used to contextualize their transformative learning experiences by revealing their prior understandings, perceptions, and confidence related to seeking and using online health information in their daily lives.

2.2.3 Semi-structured interviews

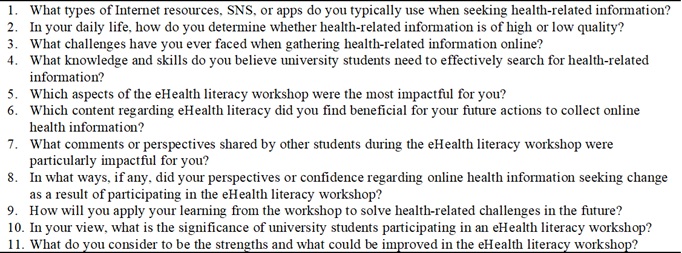

The lead author conducted semi-structured interviews (Merriam, 1998) with each participant, using an interview guide based on principles of transformative learning theory. Before conducting the interviews, the lead author explained the semi-structured interview process to each participant. All participants agreed to take part in individual, in-person interviews (one researcher and one participant), which were scheduled on dates they selected in advance. The guide included 11 core questions (Table 3) designed to explore undergraduate students’ learning experiences during the eHealth literacy workshop. In addition to these structured questions, the researcher posed supplementary unstructured follow-up questions tailored to participants’ responses. All questions were developed to gain deeper insights into instructional methods and content that influenced students’ learning outcomes. Each interview lasted about 60 minutes.

Table 3. Interview guide

2.3 Data Analysis

This study employed the constant comparative method (Boeije, 2010) to analyze translated data from interview transcripts. In addition to the qualitative data source, the demographic questionnaire responses were also reviewed to obtain descriptive background information about the six participants. The responses were summarized descriptively to capture each participant’s prior knowledge, confidence, and perceived challenges in using online health information. These descriptive results were used to interpret the qualitative findings, rather than serving as a separate source of quantitative analysis. In this study, all researchers participated in the workshop, enabling them to observe students’ learning processes and interactions, which are essential elements for understanding transformative learning. This engagement provided valuable contextual insights that complemented the interview data. The constant comparative method was therefore an appropriate analytical approach, as it enabled the researchers to compare data across participants iteratively, integrate observations from the workshop, and engage in collaborative discussions to reach consensus on the emergent themes. This process strengthened the credibility and depth of the thematic interpretation.

In the analytical process, the researcher codes each data source inductively and then uses each segment of the data to (a) compare with one or more categories to identify its relevance and (b) compare with other, similarly categorized segments of data (Schwandt 2015). More specifically, the first author conducted the preliminary coding of the data. Subsequently, two additional researchers reviewed the coded data through peer debriefing sessions to minimize potential researcher bias. Following these sessions, the first researcher implemented second-round coding of key terms through the lens of transformative learning theory. During this stage, similar codes were merged (e.g., evaluation and assessment), and categorized data segments were collaboratively discussed to identify patterns of similarity and divergence. Finally, the researchers grouped the codes into thematic categories, which were further refined into recurring themes (i.e., Theme I, Theme II, and Theme III) that represent the main findings of this study (Boeije, 2010). Trustworthiness was established through member checking and peer debriefing (Merriam, 1998).

Table 4. Results of the questionnaire regarding participants’ eHealth literacy

3. Results

A review of the demographic questionnaire results on eHealth literacy (Table 4) showed that although some participants believed they knew how to search for online health information to address their personal health concerns, they generally lacked confidence in evaluating its reliability and quality. This perceptual gap was further explained by qualitative findings, which identified three major, interrelated, and complex themes: (Theme I) learning about searching strategies to identify problematic assumptions, (Theme II) task-oriented learning to develop evaluation skills, and (Theme III) necessity of learning eHealth literacy for students who live alone.

3.1 Theme I: Learning about searching strategies to identify problematic assumptions

All participants believed that learning about searching strategies during the workshop was valuable for uncovering their problematic assumptions regarding accessing online health information. They engaged in critical self-reflection when they recognized a mismatch between their newly acquired knowledge and their prior beliefs about effective searching. More specifically, during the workshop, participants examined their habitual searching practices, such as relying on the first results shown, trusting the websites of well-known companies, or focusing solely on a single website. As they encountered new learning, they began to question the adequacy of these approaches and realized the need for more deliberate strategies. This process encouraged participants to transform their beliefs about searching for online health information and to adopt multiple strategies in their future daily lives. For example, Mr. Nori explained that learning about searching strategies prompted him to critically reflect on his own tendency to depend solely on one website for health information. He explained:

Before the workshop, I believed that checking just one website was enough to find the health information I needed. For example, since last year, I have lost six kilograms without doing any regular exercise. I became a little worried about this change, so I searched on Google. The first result I saw said it was not a big problem, so I immediately assumed everything was fine. However, during the workshop, I realized that this searching strategy was problematic because I never compared information from different websites to check their accuracy. Learning about effective search strategies helped me recognize a weakness in my approach and understand the importance of consulting multiple sources to find appropriate and reliable health information. (Mr. Nori Interview)

Mr. Nori realized that he needed to transform his searching strategy by consulting and comparing multiple sources in order to identify reliable health information. Another participant, Ms. Rio, explained that the critical questions (asked by the instructor) during the workshop led her to challenge her prior assumption that a well-known company’s website could always be trusted as a source of accurate health information. She said:

Before the workshop, I believed health information released by major companies was always reliable. However, when the instructor asked us a controversial question at the end of the lecture, I realized this assumption was misguided. He asked, “If a well-known company appeared in the news because of a major scandal, how would that change your trust in them?” That question prompted me to reflect deeply and recognize the importance of critically evaluating information rather than accepting it at face value. […] In particular, I believe university students must develop eHealth literacy, since many reach the age when they are legally permitted to drink and smoke, which may negatively affect their health. Therefore, learning effective search strategies is essential to help students access reliable health information by themselves. (Ms. Rio, Interview)

Ms. Rio stressed the importance of searching skills for undergraduate students to access accurate information and to identify both positive and negative influences on their health, especially as they experience major lifestyle changes (e.g., legally allowed to drink and smoke from the age of 20 in Japan). Additionally, Mr. Somi emphasized that learning search strategies should include the topic of using SNS, such as TikTok, as he realized he had previously accepted health information passively without considering its personal relevance. He said:

Before the workshop, I often watched TikTok by casually scrolling and paying only partial attention, and I tended to accept health information as it was presented without critical thinking. However, during the workshop, I realized that I need to consider the personal relevance of the health information I find from now on. If the information does not fit my own situation and health needs, I risk being misled by inaccurate advice and wasting my time. (Mr. Somi Interview)

Mr. Somi pointed out the risk of using SNS to access large amounts of health information, much of which may not match the individual health needs of university students (Kirkpatrick & Lawrie, 2024). He therefore argued that learning search strategies should address not only websites but also the SNS platforms widely used by students.

3.2 Theme II: Task-oriented learning to develop evaluation skills

Before the workshop, the participants admitted that they had rarely engaged in intentional evaluation of online health information and were uncertain which factors to consider when making evidence-based judgments. During the workshop, they recognized task-oriented learning as valuable because it transformed their perspective and strengthened their evaluation skills. Task-oriented learning involves hands-on experiential activities designed to accomplish specific tasks (Limbo & Limbo-Rivera, 2024). In this study, participants applied the CRAAP test as a practical tool that deepened their understanding of the evaluation process and encouraged a shift in their approach to evidence-based decision-making. For example, Mr. Nori explained that task-oriented learning helped him recognize the importance of evaluation by examining online health information more carefully and systematically. He explained:

Before the workshop, I had never considered evaluating online health information and was unsure of how to do it. Through the task-oriented activity using the CRAAP test, I realized that evaluation is an important process because it helps me examine content more deeply and determine its trustworthiness. From this experience, I recognized that I had previously overlooked important factors when checking the information, such as who authored the information and when it was released. This practical experience was beneficial in broadening my perspective on how to assess the trustworthiness of online health information. (Mr. Nori Interview)

Mr. Nori appreciated the use of the CRAAP test, as it enabled him to identify key factors, such as the author and the release date, that should be examined during the evaluation process. Similarly, another participant, Mr. Ken, explained that the task-based learning experience helped him resolve the concerns he often felt when encountering conflicting health information in his daily life. He said:

Sometimes, I felt stuck when searching for information about protein drinks. Some sites claimed they were beneficial for me, while others warned that they could lead to weight gain, and I didn’t know which to trust. In the workshop, I realized I could solve this problem by learning how to critically evaluate online health information. Applying the CRAAP test helped me understand the importance of seeking evidence-based data, rather than just considering who published the information. Since then, I’ve started checking references more carefully so I can rely on information that’s supported by solid evidence. (Mr. Ken, Interview)

Mr. Ken acknowledged that he gained a new perspective to focus on evidence-based data when judging the accuracy of online health information. He learned that scientific evidence helps him distinguish appropriate information from multiple sources. To promote task-oriented learning, Mr. Jyo emphasized the importance of collaborative activities with peers rather than working individually. He believed that collaboration exposed him to different viewpoints, challenged his assumptions, and encouraged critical reflection, offering valuable opportunities to develop practical ideas for evaluating information. He said:

Working in a group with the CRAAP test really helped me learn how to evaluate online health information more effectively. I feel this kind of activity works better for university students when it’s done through group discussions rather than alone. Talking with peers gave me different perspectives that challenged my assumptions and made me reflect more critically on my own thinking regarding evaluation. This activity helped me check whether my evaluation methods and results were actually appropriate. (Mr. Jyo Interview)

Mr. Jyo explained that exchanging opinions with peers during the evaluation process had played a crucial role in helping him question his own assumptions, engage in critical thinking, and refine his evaluation approaches.

3.3 Theme III: Necessity of learning eHealth literacy for students who live alone

All participants recognized through the workshop that undergraduate students who live alone need to develop eHealth literacy. In this study, most participants (except Mr. Ken) lived with their parents and realized that, at home, they often received health-related support without being aware of it. However, during peer discussions in the workshop, they came to understand that students who live alone carry greater responsibility for searching, evaluating, and applying health information due to less support from parents. This exchange of perspectives allowed them to critically reflect on their own situation and recognize that eHealth literacy is not only essential for students currently living alone, but also for them, since they may eventually leave their parents in the future. For example, Ms. Chika explained:

When I exchanged opinions with other students, I was surprised to learn that those who live alone have different perspectives and needs when using online health information. Since I live with my parents, I can easily ask them for advice whenever I need information. In contrast, students who live alone carry the responsibility of deciding for themselves which online information to trust and use. I feel this is a significant difference. Therefore, it is especially important for university freshmen who live alone to develop strong eHealth literacy skills, enabling them to identify and apply appropriate information in accordance with their physical and mental health needs. (Ms. Chika Interview)

Ms. Chika realized that students who live alone have fewer opportunities to ask questions or discuss health-related concerns with their parents. Therefore, she believed that university courses should offer students (at the earlier stages of university life, such as freshmen) who live alone educational opportunities to gain eHealth literacy, enabling them to maintain their health independently. As a student living alone, Mr. Ken shared his own experience after undergoing surgery and emphasized the challenges he faced in gathering health information on his own. He explained:

I live alone now, and I believe university students in the same situation should develop eHealth literacy because they must search, select, and use health information independently. When I was a freshman, I underwent surgery on my left leg. After the operation, the doctor instructed me to avoid moving it as much as possible. To cope, I searched online for ways to control body movement while sleeping so my leg would not move or touch anything. I also looked up nutrition information to support my recovery. Living alone made it feel like a heavy burden to gather and judge all this health information by myself. And I felt much loneliness. Because of this experience, I realized during the workshop that learning eHealth literacy is essential for students who live alone to feel more confident in collecting reliable health information. (Mr. Ken Interview)

Mr. Ken reflected on his prior experience, which illustrates his transformative learning in recognizing the importance of eHealth literacy opportunities for students who live alone, as a way to reduce emotional and psychological burdens (e.g., loneliness). In contrast, although Ms. Rio currently lives with her parents, she emphasized the need for spaces and opportunities to apply eHealth literacy in preparation for the time when she will live independently. She said:

After the workshop, I tried to put what I learned into practice at home, but it wasn’t easy. For example, one day I looked up information about healthy meals and calories to suggest better nutrition to my parents. But they just said, ‘No, you don’t need to worry about that.’ Even when I wanted to apply health information, I felt I didn’t have the chance because my parents stopped me. Still, I know that one day I’ll move out and live on my own. That’s why I believe I need opportunities for self-determination to practice searching, evaluating, and applying health information to care for my well-being. I think this kind of opportunity is especially important not only for students who live alone but also for those still living with parents. (Ms. Rio Interview)

Ms. Rio believed that simply learning how to search for and evaluate health information was not enough for her living situation, as she received health-related support from her parents. She felt that the eHealth literacy workshop should provide students with practical opportunities to promote their self-determination skills, enabling them to actually apply health information in daily life.

4. Discussion

For all participants, the concept of eHealth literacy was a new area of learning, and they had little prior experience sharing their everyday practices of searching for, evaluating, and using online health information with others. Based on the demographic questionnaire, the participants generally reported low confidence in finding, accessing, and using appropriate online resources when seeking health-related information. This does not mean that they rarely used the Internet, SNS, or apps. Rather, as the interview data indicated, they recognized that although they regularly attempted to search for online health information when needed, they lacked the knowledge and skills necessary for conducting effective searches. Prior studies similarly note that university students often have limited eHealth literacy despite frequent Internet use (Mitsutake et al., 2011). Therefore, the participants were suitable for this study because their initial knowledge and skill gaps created meaningful opportunities during the workshop to engage in the reflective processes central to transformative learning. The findings suggest that learning effective searching strategies should be an essential component of eHealth literacy workshops, as it enables students to recognize problematic assumptions and improve their performance. Based on transformative learning theory (Mezirow, 1997), students experienced disorienting dilemmas when they realized the inadequacy of habitual practices, such as relying on the first search result, trusting well-known companies without further evaluation, or accepting information from SNS without considering its relevance.

The findings highlight the importance of critical questioning as a pedagogical strategy to promote undergraduates’ self-reflection on searching habits and beliefs. Students noted that instructor-posed questions (e.g., scenarios challenging the trustworthiness of well-known companies) played a pivotal role in stimulating reflective questioning (van Seggelen-Damen & Romme, 2014), which helped them interrogate assumptions and problem-solving processes through both individual and collective reflection. Individually, students reconsidered unconscious assumptions to move beyond personal knowledge boundaries and adopt multiple search strategies. Collectively, comparing diverse approaches in group activities encouraged respectful dialogue, co-construction of meaning, and recognition of multiple valid perspectives, which offered insights for improving information-seeking behaviors (Elliott & Reynolds, 2012). Accordingly, we recommend that future eHealth literacy workshops integrate critical questions to transform students’ searching behaviors by adopting effective strategies while reducing reliance on unexamined assumptions.

The findings highlight the growing need to incorporate SNS platforms into eHealth literacy education. While prior research emphasized traditional web-based searching (Kim & Xie, 2017), students in this study reported that much of their daily exposure occurs through SNS, where evaluating credibility and relevance is particularly challenging (Kirkpatrick & Lawrie, 2024). Vosoughi et al. (2018) demonstrated that false news spreads more rapidly than verified information via SNS, largely due to its emotional appeal and immediacy. Consistent with this, students in this study admitted they often consume SNS content without careful evaluation, facilitated by features such as swiping and random access. Prior studies have reported the association between unverified SNS health content with risky health behaviors among young adults, especially during the period of students’ lifestyle shift from earlier stages (Moorhead et al., 2013). These findings suggest that eHealth literacy education should also address SNS-based information, where rapid consumption (e.g., swiping, random access) may hinder careful evaluation.

The undergraduate students in this study demonstrated that task-oriented learning, which emphasizes hands-on experiential activities designed to accomplish specific tasks (Limbo & Limbo-Rivera, 2024), was effective in transforming perspectives and strengthening evaluation skills. As Ke et al. (2023) note, task-oriented learning fosters problem-solving by enabling students to consolidate, internalize, and apply newly acquired knowledge. In this study, applying the CRAAP test as a task-oriented tool provided a framework for systematically assessing online health information, which students reported helped them feel more able to distinguish credible sources. Ellison and Sato (2021) argue that transformative learning occurs when learners are given opportunities to test and apply new perspectives. Consistent with this view, the CRAAP test activity allowed students to engage in evidence-based evaluation while reflecting on their prior assumptions. Through this process, they recognized previously overlooked factors such as authorship, publication date, and scientific evidence, essential for making reliable judgments while examining potential biases (Muis et al., 2022). Therefore, they regarded the CRAAP test as a practical instrument for addressing everyday challenges of evaluating conflicting health information (e.g., when one source presents positive claims and another negative ones).

The findings highlight the importance of collaborative group work in enhancing task-oriented learning. Sweet (2022) notes that discussion-based activities foster reflection and the exchange of diverse perspectives. Consistent with this, students reported that small-group discussions during the CRAAP test encouraged them to share evaluation results, compare approaches, and identify both successful and unsuccessful strategies. Such discussions provided an environment where students actively participated in learning (Badge et al., 2024), thereby deepening individual reflection and strengthening the development of more robust evaluation practices. Accordingly, the findings suggest that integrating evidence-based tools such as the CRAAP test into task-oriented, discussion-based activities may offer a helpful approach for supporting students’ evaluation skills, based on their reported experiences during the workshop.

The undergraduate students in this study found that those living alone may face unique challenges in health-related information-seeking compared with peers living with parents. Through peer discussions, students recognized that living with family often provides implicit health-related support, whereas living alone increases responsibility for searching, evaluating, and applying information. This reflective process aligns with transformative learning theory (Mezirow, 1997), as students (including those living alone and with family) reconsidered how their living circumstances shape their everyday information practices. Zahedi et al. (2022) noted that loneliness negatively affects students’ physical and mental health by hindering adjustment and reducing access to close relationships. For example, one student (Mr. Ken) described experiencing loneliness after surgery and the emotional burden of independently searching for trustworthy information. This indicates that students living alone may face greater difficulty managing their health information independently and may feel more isolated. Although this study did not directly examine loneliness and included only one participant who lived alone, these insights tentatively suggest that providing early opportunities to learn eHealth literacy, such as through freshman orientation or first-year seminars, may be beneficial for students who have limited daily guidance at home.

In addition to challenges experienced by students living alone, some participants reflected on how living with family also shaped their opportunities to apply eHealth literacy skills. For example, one participant (Ms. Rio) acknowledged limited opportunities to apply eHealth literacy to improve her nutrition due to parental control at home. This aligns with Cahill and Bulanda’s (2009) argument, enabling students to make informed decisions, solve problems, set goals, and develop action plans is an important aspect of helping them acquire knowledge that fits their individual health needs. Therefore, these findings highlight the value of designing eHealth literacy workshops that acknowledge varied living arrangements and provide optional opportunities for students to practice decision-making when relevant.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the transformative learning experiences of Japanese undergraduate students during an eHealth literacy workshop. The findings emphasize the importance of prioritizing eHealth literacy in Japanese universities to prevent students from engaging in risky health information practices. However, this study has several limitations, including a small sample size, limited participant backgrounds, and reliance on a narrow range of data sources (e.g., the absence of group discussion data from the workshop). For instance, although all participants were undergraduate students majoring in economics, the study did not examine how the characteristics of this major may have shaped their eHealth literacy learning, nor did it allow for comparisons across different academic disciplines. Therefore, future research should incorporate both qualitative and quantitative data to enhance the generalizability of the findings and provide more robust insights for researchers and practitioners seeking to develop effective eHealth literacy education for undergraduate students. In the emerging era of Artificial Intelligence and the smart society, where students are increasingly required to determine the reliability of information independently, it is essential that they develop the skills to search for, evaluate, and apply health information effectively. Therefore, we hope that the findings of this study will contribute to the development of both formal and informal eHealth literacy education opportunities in Japanese universities, fostering students’ ability to become effective and responsible seekers of online health information.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.T. Y.Y. and C.M.; methodology, T.T.; formal analysis, T.T.; investigation, T.T.; data curation, T.T. Y.Y. and C.M; writing—original draft preparation, T.T.; writing—review and editing, Y.Y. and C.M.; supervision, Y.Y.; project administration, T.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by grants from Fukuyama University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Fukuyama University (protocol code H-01, 17th March 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all the participants for their cooperation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Adeoya A.A. (2025). Exploring health literacy among Japanese and international university students in Japan: A comparative cross-sectional study. Journal of migration and health, 11, 100334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmh.2025.100334

American College Health Association. (2024). American college health association’s national college health assessment. https://www.gavilan.edu/student/health/acha_ncha.php (accessed 10 December 2025)

Badge, A., Chandankhede, M., Gajbe, U., Bankar, N.J., & Bandre, G.R. (2024). Employment of small-group discussions to ensure the effective delivery of medical education. Cureus, 16(1), e52655. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.52655

Berkman, N.D., Sheridan, S.L., Donahue, K.E., Halpern, D.J., & Crotty, K. (2011). Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Annals of internal medicine, 155(2), 97–107. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005

Boeije, H.R. (2010). Analysis in qualitative research. Sage Publications.

Brownell, S.E., Hekmat-Scafe, D.S., Singla, V., Chandler Seawell, P., Conklin Imam, J.F., Eddy, S.L., Stearns, T., & Cyert, M.S. (2015). A high-enrollment course-based undergraduate research experience improves student conceptions of scientific thinking and ability to interpret data. CBE life sciences education, 14(2), ar21. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.14-05-0092

Cahill, S.M., & Bulanda, M. (2009). Using transformative learning theory to enhance professional development. Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice, 7(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.46743/1540-580X/2009.1231

Chen, X., Ariati, J., McMaughan, D.J., Li, M., & Kreps, G. (2024). How college students evaluate the quality of online health information: A qualitative study. Health Behavior Research, 7(4), 7. https://doi.org/10.4148/2572-1836.1250

Closs, L., & Antonello, C. S. (2011). Transformative learning: Integrating critical reflection into management education: Integrating critical reflection into management education. Journal of Transformative Education, 9(2), 63-88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344611429129

Ellard, O.B., Dennison, C., & Tuomainen, H. (2023). Review: Interventions addressing loneliness amongst university students: a systematic review. Child and adolescent mental health, 28(4), 512–523. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12614

Elliott, C.J., & Reynolds, M. (2012). Participative pedagogies, group work and the international classroom: An account of students’ and tutors’ experiences. Studies in Higher Education, 39, 307-320. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2012.709492

Ellison, D.W., & Sato, T. (2021). Curriculum negotiation in an undergraduate fitness education course for transformative learning. International Journal of Kinesiology in Higher Education, 7(1), 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/24711616.2021.1946451

Hamilton, P.R., Hulme, JA., & Harrison, E.D. (2021). Experiences of higher education for students with chronic illnesses. Disability & Society, 38(1), 21–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2021.1907549

Hodge, S. R., Tannehill, D., & Kluge, M. A. (2003). Exploring the meaning of practicum experiences for PETE students. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 20(4), 381-399. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.20.4.381

Kim, H., & Xie, B. (2017). Health literacy in the eHealth era: A systematic review of the literature. Patient education and counseling, 100(6), 1073–1082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.01.015

Kirkpatrick, C.E., & Lawrie, L.L. (2024). TikTok as a source of health information and misinformation for young women in the United States: Survey Study. JMIR infodemiology, 4, e54663. https://doi.org/10.2196/54663

Ke, L., Xu, L., Sun, L., Xiao, J., Tao, L., Luo, Y., Cao, Q., & Li, Y. (2023). The effect of blended task-oriented flipped classroom on the core competencies of undergraduate nursing students: a quasi-experimental study. BMC nursing, 22(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-022-01080-0

Limbo, A.B., & Limbo-Rivera, C.B. (2024). Performance level of physical education students: Basis for the development of task-based teaching strategies. Indonesian Journal of Physical Education and Sport Science, 4(4), 387-397. https://doi.org/10.52188/ijpess.v4i4.811

Meriam Library of CSU Chico. (2010). Evaluating information: Applying the CRAAP test. https://library.csuchico.edu/sites/default/files/craap-test.pdf (accessed 10 December 2025)

Merriam, S.B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow J. (1997). Transformative learning: theory to practice. New Direction for Adult & Continuing Education. 74, 5-12. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.7401

Mezirow, J. (2018). Transformative learning theory. In K. Illeris (Ed.), Contemporary theories of learning: Learning theorists in their own words (2nd ed., pp. 114–128). Routledge.

Mitsutake, S., Shibata, A., Ishii, K., Okazaki, K., & Oka, K. (2011). Developing Japanese version of the eHealth literacy scale (eHEALS). Japanese Journal of Public Health. 58(5), 361-371. (in Japanese)

Moorhead, S.A., Hazlett, D.E., Harrison, L., Carroll, J. K., Irwin, A., & Hoving, C. (2013). A new dimension of health care: systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. Journal of medical Internet research, 15(4), e85. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1933

Muis, K.R., Denton, C., & Dubé, A. (2022). Identifying CRAAP on the internet: A source evaluation intervention. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 9(7), 239–265. https://doi.org/10.14738/assrj.97.12670

Nagashima, Y., Inokuchi, M., Sato, Y., & Hasegawa, T. (2024). Underweight in young Japanese women over time: a longitudinal retrospective study of the change in body mass index from ages 6 to 20 years. Annals of Human Biology, 51(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/03014460.2024.2345393

Norman, C.D., & Skinner, H.A. (2006). eHEALS: the eHealth literacy scale. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 8(4), e507. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.8.4.e27

Papp-Zipernovszky, O., Horváth, M. D., Schulz, P.J., & Csabai, M. (2021). Generation gaps in digital health literacy and their impact on health information seeking behavior and health empowerment in Hungary. Frontiers in public health, 9, 635943. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.635943

Patton, M.Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Sage.

Sato, T., Haegele, J.A., & Foot, R. (2017). Developing Online Graduate Coursework in Adapted Physical Education Utilizing Andragogy Theory. Quest, 69(4), 453–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2017.1284679

Schwandt, T.A. (2015). The SAGE Dictionary of Qualitative Inquiry. Fourth Edition. Los Angeles, Calif: Sage Publications.

Stellefson, M., Hanik, B., Chaney, B., Chaney, D., Tennant, B., & Chavarria, E.A. (2011). eHealth literacy among college students: a systematic review with implications for eHealth education. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 13(4), e102. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1703

Sweet, S.F. (2022). Using guided critical reflection to discover deepened and transformative learning in leadership education. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 18(4), 600-621. https://doi.org/10.1177/19427751221118951

Takahashi, T. (2014). Youth, social media and connectivity in Japan. In The language of social media: Identity and community on the Internet (pp. 186-207). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Tomura, T., Sato, T., Miller, R.T., & Furuta, Y. (2024). Japanese elementary teachers’ experiences during online professional development regarding involvement of immigrant parents in physical education. European Physical Education Review, 30(2), 228-249. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X231199677

van Seggelen-Damen, I. CM., & Romme, A.G.L. (2014). Reflective questioning in management education: lessons from supervising thesis projects. SAGE Open, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014539167

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146–1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

Yin, R.K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Sage.

Zahedi, H., Sahebihagh, M.H., & Sarbakhsh, P. (2022). The magnitude of loneliness and associated risk factors among university students: A cross-sectional study. Iranian journal of psychiatry, 17(4), 411–417. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijps.v17i4.10690

Relevant Articles

-

Why do you recall that smelly food? Effects of childhood residence region and potential reinforcing effect of marriage

by Yoshinori Miyamura - 2026,2

VIEW -

An attempt to realize digital transformation in local governments by utilizing the IT skills of information science students

by Edmund Soji Otabe - 2025,4

VIEW -

A practical evaluation method using item response theory to evaluate children’s form of Jumping-over and crawling-under

by Yasufumi Ohyama - 2025,3

VIEW -

A Survey on BeReal among University Students: Focus on Learning Motivation and Privacy Consciousness

by Futa Yahiro - 2025,2

VIEW